This spring marks the 180th anniversary of Samuel Melvin’s birth on April 9, 1844. While the entire family would be deeply and tragically affected by the Civil War, Samuel, the fourth child and third son, went through a particularly hard time while serving in the Union Army. This is the story of his Civil War.

Asa and Caroline Heald Melvin raised four boys and one daughter in Concord. When the war began in April 1861, the oldest son, Asa (named after his father), was the first to volunteer his services to the Union Army. After his three-month term of enlistment ended, he re-enlisted and was joined by two of his younger brothers, John and Samuel. A fourth brother, James, was too young to join the army in 1861 but would enlist in 1864.

Although Samuel was born and raised in Concord, as a teenager he moved to Lawrence, MA, to work as an operative in a textile factory. He was 17 years old when he followed in his brothers’ footsteps and enlisted as a private in Company K, 1st Massachusetts Heavy Artillery.

The 1st Massachusetts spent the first three years of the war stationed in the forts around Washington, D.C. But as the spring 1864 campaign against Robert E. Lee began, the need for manpower in the field led to the transfer of many units to the front, including the Melvins and the 1st Massachusetts. Pulled out of the relative safety of the fortifications, the “heavies” soon found themselves on the battle lines in the thickest of the fighting. The battles in Virginia in 1864 would be particularly horrific as General Grant would constantly attack the Confederate army for months on end without letting up.

Samuel had a diary, but it seems that he wasn’t very good at writing things down. With 1863 ending and a new year about to commence, he made a resolution to get better at recording his thoughts: “I have not put many things down, but next year I shall be very punctilious and note [everything]...Perhaps in some future day, after I shall have passed to the spirit life, someone may take much pleasure in looking over this. Who can tell? But if I shall pass away ‘ere another year, ‘tis all for the best. With this little remark I close my diary for 1863, leaving it to the fate of time.”

Page of Samuel Melvin’s diary

| Andersonville NHSAs the Melvins’ regiment headed into Northern Virginia, Samuel noted in his diary the horrors all around him, including “lots of wounded” with “Drs. cutting them up”. The scenes of total war looked “mighty rough” to the 20-year-old. Bad food, rainy weather, sickness, Rebel shells flying overhead, unburied corpses, sleeping on the ground – Samuel reported on it all, and did his best to put on a brave face: “This is a rough life, and one that I do not like, but I shall stand it like a man.” And it was about to get a lot rougher for him.

On May 12, 1864, the Battle of Spotsylvania would begin, and the fighting would continue unabated for the next 12 days. Fighting at the Harris Farm on May 19 found the 1st Massachusetts in action for the first time. The battle was small but bloody: the Massachusetts regiment had 55 men killed, 312 wounded, and 27 missing or captured. Samuel reported that his “battalion went after the Rebs” and that “the fire was awful.” It was while helping a wounded comrade to the rear that Samuel was surrounded by Confederate troops, and the unthinkable happened; almost nonchalantly he would write in his diary, “I surrendered.”

From then on Samuel would keep a daily record of his life as a prisoner of war. The transfer from Virginia to a Georgia prisoner-of-war (POW) camp wasn’t easy, and it got off to a rough start for Samuel and the other prisoners. “Marched all day. No rations all day. It was indeed truly painful,” Samuel recorded. Still, he kept up hope that things would get better, adding, “the time is not far distant, I hope & trust, when we can reap the rewards of life” with a continued faith in “ourselves, our country, and our God.”

Herded like cattle, marching in the heat (and sometimes pouring rain), and traveling by railroad in over-crowded boxcars with little or no food and water, Samuel and the other POWs finally arrived at Andersonville prison on June 3, 1864. Almost immediately Samuel noted the “deplorable condition” of the Union prisoners. Andersonville would become notorious as the worst POW camp of the Civil War.

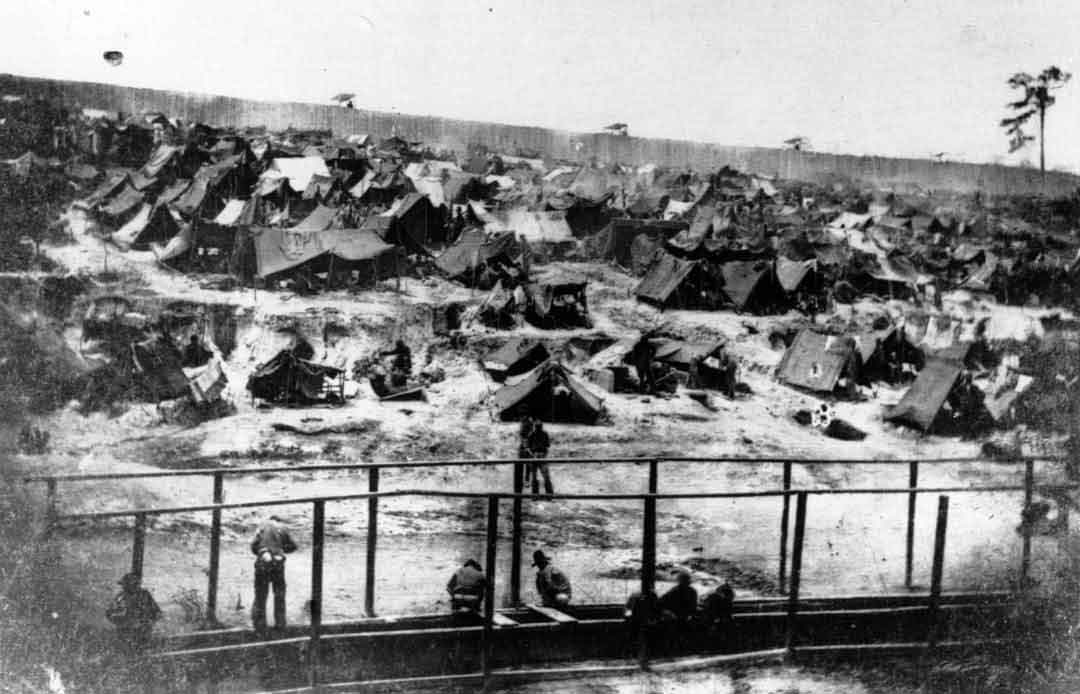

Andersonville Prison

| ©Library of CongressThe prison was a large open pen surrounded by a stockade fence. The thousands of Union prisoners kept there were subjected to the elements and did their best to shelter themselves from the scorching Southern sun. Due to overcrowding, rations were scarce and sometimes non-existent. A single creek ran through the prison yard, used by the men for their drinking water, as well as for washing up and relieving themselves. Rats and lice were rampant, as were starvation and disease; dysentery, hepatitis, pleurisy, scurvy, smallpox, and typhoid ravaged the prison population.

Samuel had no misconceptions about the fix he was in. After only two days in the camp he wrote in his diary, “If I die here, I am sure we shall die in a good cause although in a brutal way.” He had good reason to be pessimistic. By the time he’d arrived at the prison it was just over 26 acres, and some 33,000 prisoners were crammed into the pen. Death was a daily occurrence, and from February 1864 to May 1865, thirteen thousand Union soldiers would die and be buried there.

Samuel did his best to keep his hopes up, but his diary shows the emotional rollercoaster that he (and no doubt the other prisoners) went through daily. Monotony and boredom were the order of the day. “There is no difference here, one day from another,” he commented. “All is sadness and sorrow,” he wrote another time. “I am discouraged.” “Why do I keep sighing? Because I can’t help it.” Each day was one of despair and sadness for the young man trapped in “this pen of insatiate misery.”

By the middle of the summer, Samuel was suffering from dysentery. It was so bad that he was unable to write in his diary. To be deathly ill (without any sort of medical treatment available) with men dying all around him must have been frightening. Still, when he was well enough to write he would give himself pep talks; “I am bound to try my best to live until I can get out of this bull-pen, for I want to see my folks at home… I am sorry to die here, or stay here longer”. Seeing a comrade die, he noted, “Fairman died this morning. Last evening he was quite smart. I never saw men slip off so easy as they do here. They die as easy as can be.”

Summer into autumn saw Samuel getting worse. For 11 days his diary was blank, but on Thursday, September 15, 1864, he wrote:

“Laid on my back all day. Eat not much, can’t eat much…I am lying in a tent on my rubber blanket…the tent and blankets are just as full of lice and fleas as ever can be. As things look now, I stand a good chance to lay my bones in old Ga., but I’d hate to [sic] as bad as one can, for I want to go home.”

That would be Samuel’s last entry. He died ten days later, on September 25, 1864. He was buried in Lot 9735 at the prison, where he remains to this day. But he is not forgotten. A memorial to Samuel and his brothers, Asa and John, sits in Concord’s Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. His diary is in the collection of the Andersonville National Historic Site. He would be pleased to know that since his death in 1864 many researchers of a “future day” have taken “much pleasure in looking over” his diary and telling the story of this Concord hero.

.webp?height=576&t=1721414148&width=auto)