Thirteen-year-old Tasun quietly slipped away from her father Tahattawan’s clan counsel to sit on the rocky prominence called Egg Rock at the confluence of the rivers to consider how her world was changing. Shortly before she was born, stories began circulating among the Nipmuc tribes of strange landless white men in wooden boats big enough to hold a whole village, trading with Indigenous people along the eastern shore of Turtle Island. Those who traded with them could sometimes receive metal and manufactured goods far beyond the technical ability of her people. Still, such trading often left death in its wake, either from outbreaks of disease or young warriors being captured, killed, or enslaved. A particularly virulent outbreak of disease among the Mysticke clan now brought Nanepashemet, supreme sachem of the Massachusetts Confederacy, and his wife Saunkskwa to Musketaquid (known today as Concord) for their own safety.

Tasun’s heart leapt when she discovered that Waban, a year older than her and the son of Wibbacowet, the powerful spiritual and wisdom teacher of the Massachusetts tribe, had come with them. Tasun was enamored with Waban and blushed when he was near her. Now Waban also slipped away to join Tasun in the dark, and their teenage romance began. Two years later, Nanepashemet died in battle fighting their sworn enemies the Abenakis, allies of the French white men further north. Saunkskwa of Mysticke rose to supreme sachem of the Massachusetts, with her sons John Wonohaquaham, James Montowompate, and George Wenepoykin serving as chiefs under her leadership.

Saunkskwa married Wibbacowet, thereby adopting Waban as her stepson. Born to be a spiritual and wisdom teacher, Waban’s name meant the Wind or Breath of God. Waban married his love, Tasun, and their union was celebrated with much joy and feasting. The young couple moved to the abandoned Indigenous village of Nonantum, where the Mishaum River flowed into the sea.

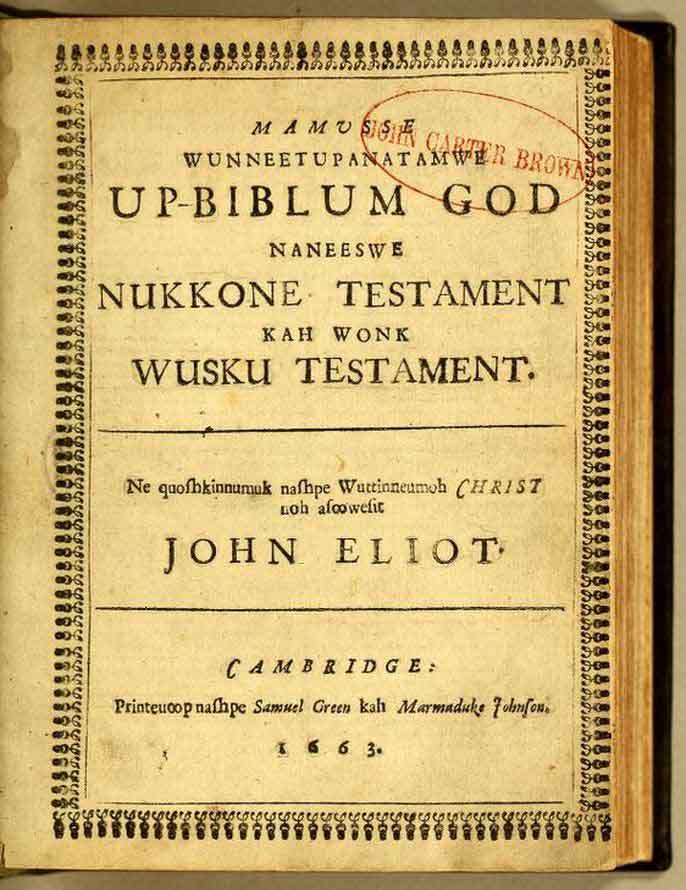

John Eliot Bible, Cambridge, 1663

| Public domain. https://archive.org/details/mamussewunneetup00elio/page/n5/mode/2upWaban befriended William Blaxton (Blackstone), a Cambridge-educated Christian minister living nearby in the abandoned Indigenous village of Shawmut. They taught each other their languages and spiritual orientations. Ten years later, when the Massachusetts Bay Company received a royal charter to settle the Mass Bay and points west, Waban took the Christian name of Thomas and served as translator between his stepmother Saunkskwa and Governor John Winthrop. Winthrop declared the twenty-eight-year-old Waban spiritual governor for all Indigenous tribes within the Massachusetts and Nipmuc Confederacies. As a result, Waban became good friends and a frequent traveling companion with the Christian missionary Rev. John Eliot. Along with Nipmuc James Printer, Waban helped translate the Bible into Algonquin. Cross-cultural friendships made living together and prospering through trading animal skins and food for English manufactured goods possible.

When militia Captain Simon Willard and Rev. Peter Bulkeley received permission from the Massachusetts General Court in 1635 to settle Concord at Musketaquid, it was Saunkskwa, Tahattawan, John Tahattawan, Tasun, and Thomas Waban who negotiated the terms with Willard and Bulkeley. Two years later, when the colonists dammed the brook to build a mill and tannery on the site, destroying an important Indigenous-built fish weir in the process, Bulkeley and Willard offered more gifts to Saunkskwa and Tahattawan for the damage it caused.

Sarah Willard and Tasun raised their children on Nashawtuc Hill while their husbands were often away traveling. Their sons, Samuel and Weegrammomenet, both attended Harvard. Samuel would become an ordained minister and eventually president of Harvard. Waban and Tasun’s son became Simon Willard’s scout.

Fifty years later, great-grandmother Tasun returned to Egg Rock to look back over a long and eventful life. Thomas Waban had become an ordained Christian minister and founder of the “Praying Indian” town of Natick, where her grandson Thomas Waban III was a selectman and Indigenous leader. Her Harvard-educated son Weegrammomenet had led the Christian Indigenous forces as Captain Thomas Waban under Major Simon Willard in King Philip’s War, which meant that even though her family was rounded up and incarcerated on Deer Island for the latter part of the war, fewer of her immediate family died or were sold into slavery than happened with other Indigenous families.

When her beloved Waban died in 1685, Tasun assumed the title of Saunkskwa of Nashawtuc, while her niece Sarah Tahattawan Dublet was Saunkskwa of Nashoba, and her stepbrother George Wenepoykin the sachem of Indigenous Natick, but these were now largely empty leadership titles that would pass away in the next generation. She worried about her newborn great-grandson Thomas Waban IV who grew up to be a sailor, changed his name to Ward, and went to sea on a New Bedford whaling ship. Life has strange twists and turns.

Tasun thought back over her long life as a carefree girl growing up on Nashawtuc Hill, as a young wife and mother teaching Sarah Willard about indigenous herbs, then joining her husband Waban for long philosophical conversations with Simon Willard, Rev. Blaxton, Roger Williams, and Governor Winthrop. Over her long life so much was lost, and at such a cost, yet so much was also gained. Looking back, she felt things certainly could have been better, but also could have been far worse, and she was thankful for the Musketaquid love story that carried her and Waban through the best and worst of times.

This article is based upon Rev. Dr. Jim Sherblom’s upcoming book The Stories of Concord. Whenever possible, this article draws from academic references and archives. However, the history of Concord’s Indigenous people is not well documented. Some details are courtesy of the author’s imagination.