As hostilities grew between Massachusetts and the English government in the 1770s, popular opinion was divided. Concord’s “patriot preacher,” Rev. William Emerson, spoke out for liberty and served as chaplain for Concord’s Minutemen. Meanwhile, his brother-in-law, lawyer Daniel Bliss, remained loyal to the King, and would be forced to flee for his life to Canada when war erupted in 1775.

As hostilities grew between Massachusetts and the English government in the 1770s, popular opinion was divided. Concord’s “patriot preacher,” Rev. William Emerson, spoke out for liberty and served as chaplain for Concord’s Minutemen. Meanwhile, his brother-in-law, lawyer Daniel Bliss, remained loyal to the King, and would be forced to flee for his life to Canada when war erupted in 1775.

When Massachusetts stood on the brink of war in 1774, the people’s representatives met in Concord, in Rev. Emerson’s own church, to decide what to do next. They conducted much of their planning and off-the-record debate next door in the place we now call the Wright Tavern, in honor of tavernkeeper Amos Wright.

Rev. William Emerson welcomed the Provincial Congress to convene at the First Parish Meetinghouse.

| Courtesy of Concord Free Public LibraryThe path to this critical choice began with people complaining about the taxes imposed on the American colonies. These were especially onerous because the colonies had no representatives in the British Parliament, so they were taxed without the people’s consent.

But many people’s livelihoods depended on imports and exports passing through the port of Boston, and trade was tightly controlled by the British government and its private-sector partner, the East India Company. Even those not directly engaged in commerce, such as judges and other government officials, often had their salaries paid out of the taxes collected on imported tea. Resistance to British rule was not an obvious or easy choice, and many families had members on opposite sides of the argument.

Until 1774, Massachusetts expressed its resentment in acts of nonviolent protest. Even the Boston Tea Party in December 1773 was carried out with great care to avoid bodily harm, but it caused considerable property damage. One report placed the amount of tea lost at more than forty tons, worth almost £10,000 at the time.

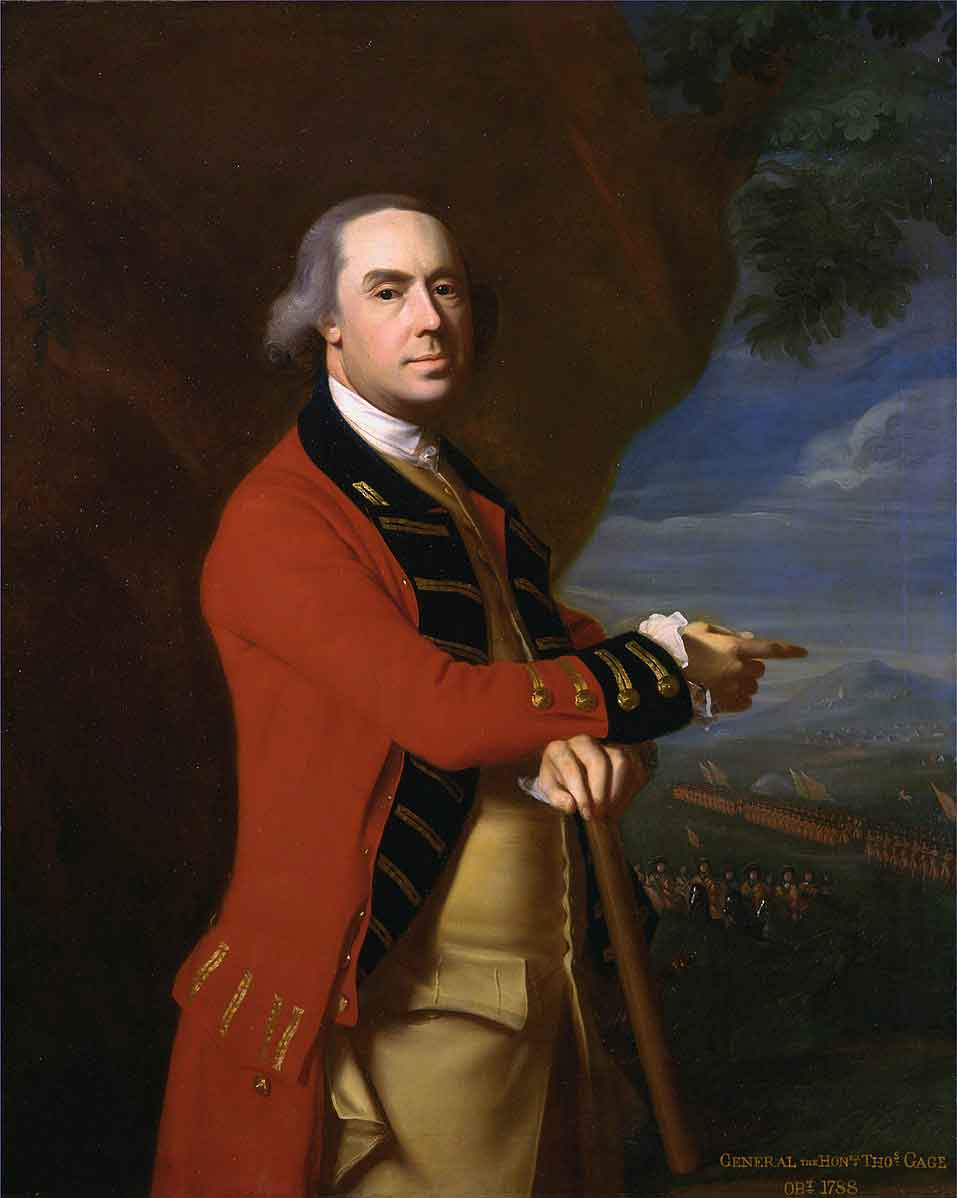

The Prime Minister, Lord North, was outraged. His response was swift and severe: “Boston had been the ringleader in all riots . . . therefore Boston ought to be the principal object of our attention for punishment.” Parliament passed what Americans called the Intolerable Acts, which closed the port of Boston, revoked the 1691 charter of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, and put Massachusetts under military rule. The elected government was replaced with a mandamus council under the control of Gen. Thomas Gage, and thousands of soldiers were deployed to enforce his orders.

Many people lost their income when the port of Boston closed. All saw their way of life endangered when they lost the right to self-government through elected representatives and Town Meetings. Were they ready to move beyond mere protest and meet these threats with force? Rev. William Emerson thought so; his loyalist brother-in-law did not.

Gen. Thomas Gage’s effort to suppress opposition in the Massachusetts assembly provoked the formation of the Provincial Congress. Portrait by John Singleton Copley, ca. 1768

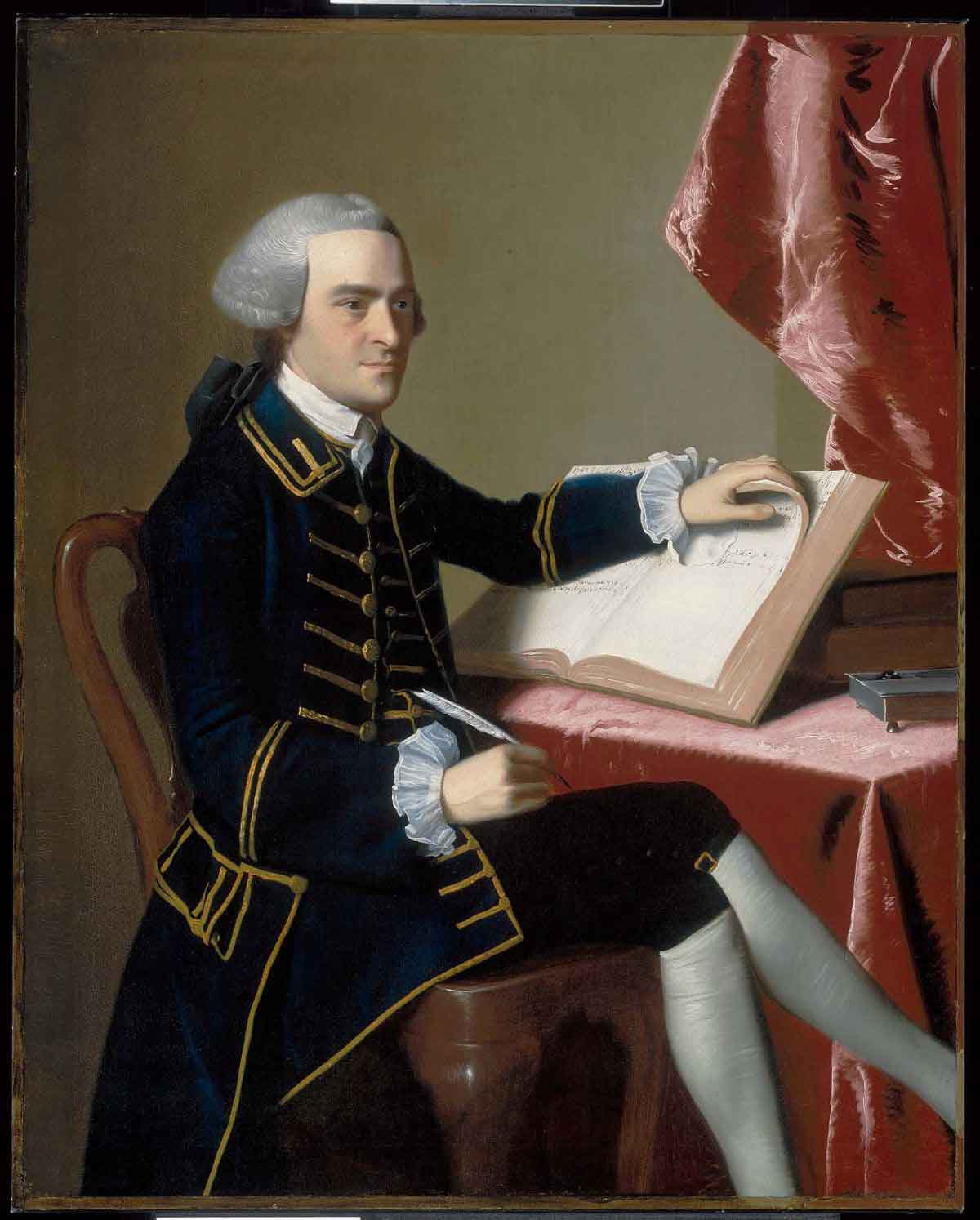

| Public domainIn September 1774, Gen. Gage had ordered the elected assembly to meet in Salem, but a few weeks later, sensing the growing opposition, he canceled the meeting. Ninety representatives showed up anyway. Since Gage and his councilors were absent, they regarded Gage’s authority as void and declared themselves the effective (if not strictly legal) government of Massachusetts, naming themselves the Provincial Congress and electing John Hancock as its president.

On October 7, the Provincial Congress met in Concord. The town offered plenty of accommodations because travelers often came here to do business at the courthouse. The most conveniently located of these was the tavern operated by Amos Wright on the Bay Road (now Lexington Road), just a few steps from the First Parish meetinghouse. The meetinghouse was the biggest building in town, and the minister, William Emerson, was a staunch patriot. He welcomed the Provincial Congress to meet there and invoked God’s blessing on their proceedings.

John Hancock presided at the Massachusetts Provincial Congress in 1774. Portrait by John Singleton Copley, 1765

| Public domainConcord had the advantage of being inland. The British occupation force was concentrated in and around Boston, and their ubiquitous presence had a chilling effect on political dissent. Farther west, patriotic sentiment flourished. Concord was not without its loyalists—Rev. Emerson’s brother-in-law Daniel Bliss was a prominent example—but the town was generally hospitable to the Provincial Congress, especially the tavernkeepers who did a brisk trade providing food and lodging for the delegates.

The Provincial Congress did not initially set out to form an independent nation. Some delegates held more radical views than others, but their immediate concern was to restore the rights of self-government that had been in place since 1691 and been revoked by the Massachusetts Government Act only a few months before. But in September, Gen. Gage had sent more than 250 soldiers to Winter Hill (in present-day Somerville) to seize the militia’s supply of gunpowder and hold it at Castle William in Boston Harbor. It appeared that an arms race had begun between the British Army and the provincial militias, and that was a race Massachusetts could not afford to lose.

In Wright’s tavern, the debate was no longer about a burdensome tax; it was now about how to meet the very real threat of military aggression. And here in Concord, the Provincial Congress chose to meet the threat head-on. They directed towns to establish Minute Companies—the elite fighting units of the local militias—and to stockpile weapons, ammunition, and “all kinds of warlike stores, sufficient for an army of fifteen thousand.”

Could they have imagined how radical that action was? The measures they deemed expedient for self-defense would result in an eight-year war, the birth of an independent nation, and a model of democracy that has taken root all over the world.

This article made possible with the support of the Wright Tavern Legacy Trust.