One April morning in 1872, William Brewster (1851-1919) took the train from Cambridge to Concord to go birdwatching with a friend. Making their way to a nearby farm, a local resident expressed surprise at their coming all the way from Boston to hear a Woodcock sing. The journey was worth it, as Brewster later recorded in his journal:

“In a few moments we heard the whistling of wings as the bird rose, and the next instant I saw him outlined against the Western sky, mounting straight up. [The bird] then began his song, an indescribable warbling mixture of liquid sounds. I was almost beside myself with excitement and pleasure and listened breathlessly for another repetition.”

William Brewster’s keen observations and poetical descriptions of birdlife made him one of the most important figures in the field of ornithology. Born and raised in Cambridge, Brewster dedicated his life to the study of birds and their habitats and later made a home for himself along the banks of the Concord River. As the first president of Mass Audubon, Brewster was also a fierce advocate for the protection of birds against commercial hunting and habitat loss. While his public legacy encompasses legislation, articles, books, and photography, it now includes a portion of the landscape he loved so dearly. In 2019, Mass Audubon received 143 acres of Brewster’s original property and renamed the site Brewster’s Woods Wildlife Sanctuary.

The Concord Museum is collaborating with Mass Audubon to tell Brewster’s story in a special exhibition in the Wallace Kane Gallery at the Museum March 4, 2022, through September 5, 2022. Alive with Birds: William Brewster in Concord will highlight works from the Museum of American Bird Art by acclaimed artists such as John James Audubon, Frank Weston Benson, and Anthony Elmer Crowell.

• • •

As a youth, William Brewster explored the fields, farms, meadows, and marshes just beyond his home on Brattle Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, collecting eggs, nests, and bird specimens to study. Rather than follow his father’s footsteps into banking, Brewster remained passionately devoted to ornithology, of which he was primarily self-taught. He founded the Nuttall Ornithological Club in 1873 with a group of like-minded enthusiasts, which later grew into the American Ornithologists’ Union. After his marriage to Caroline F. Kettell in 1878, Brewster built a new house in Cambridge, which included a library and museum to hold his growing collection of mounted birds. He became curator of mammals and birds at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University in 1885.

Brewster had been a frequent visitor to Concord since the 1860s, exploring the area with his lifelong friend Daniel Chester French. In 1890, he bought a tract of woodland on the Concord River, known as Ball’s Hill. He soon added to it Holden’s Hill, Davis’ Hill, and the John Barrett Farm, with a farmhouse situated on Monument Street dating back to the eighteenth century. The combined property spanned 300 acres and Brewster renamed it October Farm.

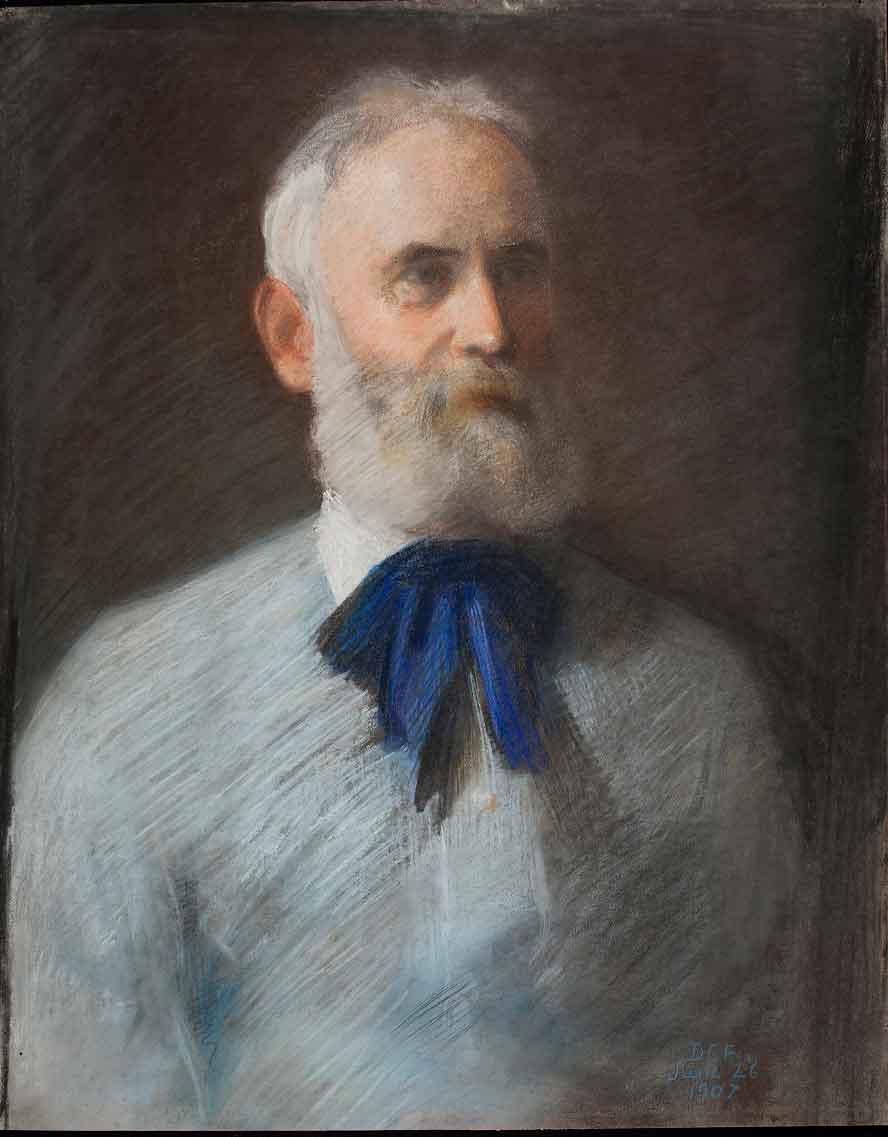

Portrait of William Brewster by Daniel Chester French, 1907.

| Chapin Library, Williams College, Gift of the National Trust for Historic PreservationBrewster’s time at October Farm overlapped with his tenure as the first president of Mass Audubon, an organization founded by Harriet Lawrence Hemenway and Minna B. Hall. They advocated against the killing of birds for the sale of their feathers and successfully advanced legislation in Massachusetts to prohibit the trade of illegally hunted wildlife. This position marked a turning point in Brewster’s life, because for many years he followed the widely accepted practice of using a shotgun to collect specimens. He shot thousands of birds in the 1870s and 1880s, donating most of them to Harvard. But by 1890, Brewster grew concerned about the visible decline in bird species and population and recognized that this decline was “due chiefly or wholly to systematic persecution on the part of man.”

As an experiment, Brewster vowed not to shoot a single bird at October Farm and embraced alternate methods of observation using binoculars and cameras. He also transitioned from strictly recording empirical data on birds, used in building taxonomies, towards a more descriptive approach focused on animal behavior, songs, and habitats. Such close observation broadened Brewster’s knowledge of the differing bird species in and around Concord.

Bird observation could be a painstaking process, but William Brewster had support from Robert Gilbert, his field assistant and companion. Born in Virginia, Gilbert made his way to Cambridge as a young man and was employed by Harvard Medical School, where he assisted with the care of animals in the laboratories. He was hired by Brewster around 1897 when he was 27 years old. As a Black man, Gilbert’s participation in the field of ornithology was rare for the time; however, he became an experienced and accomplished birder, able to identify different species from both sight and sound.

During a period of 23 years, Robert Gilbert’s duties evolved from general camp manager to skilled ornithological associate. Gilbert is often credited as a landscape photographer, though only a handful of photos are directly attributed to him. It is more apt to say that he was fully involved in documenting the wildlife in and around October Farm. Brewster describes dozens of scenarios where he and Gilbert spent the day taking photographs, and Gilbert was often in charge of staging encounters with birds, locating their nests, and startling them so they could be caught by the camera in mid-flight. In other cases, he interacted with birds to soothe them. In one incident, a young owl, described as “surly and untamable” finally learned to tolerate Gilbert “and took raw meat from his fingers thanklessly enough but without much active resentment.” Gilbert visited and fed the bird daily for a week, which finally allowed Brewster to photograph the bird up close. After Brewster’s death in 1919, Gilbert went on to work for the Museum of Comparative Zoology and became an Associate of the American Ornithologists’ Union. In one letter to a colleague, Gilbert reminisced about his time with Brewster, which he called “the good old days.”

William Brewster spent his last day in Concord listening to “a glad choir of delightful bird music.” He died two months later in July 1919, but his legacy lives on. Thanks to Brewster, and Henry David Thoreau before him, Concord has one of the longest records of bird arrival dates in North America. More than 200 ornithologists have been active in the area for the last century, inspired by Thoreau and Brewster’s contributions to the field. Selections from Brewster’s journals documenting his time in Concord were published posthumously in October Farm (1936) and Concord River (1937). Just as William Brewster forged a connection to nature during his time in Concord, Brewster’s Woods, forever protected, will now provide even greater opportunities for new generations of birdwatchers.