Have you found yourself wandering around Concord and wondering exactly how Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) is connected to the central story of the town? The philosopher’s name is everywhere, his name connected to every story somehow. He has a connection to the Revolutionary War and was also central to planting Transcendental roots deep in Concord, anchoring it as a movement, acting as the intellectual bridge to both the past and the future.

Here is a quick rundown on how his own life connects Concord’s past to its future.

A BRIDGE TO THE PAST

The Old Manse and North Bridge

Emerson was born in Boston, but his family had deep ties to the Old Manse, and he would spend time there as a child. His aunt, Mary Moody Emerson (1774-1863), witnessed the “shot heard round the world” as her mother held her, watching the fight on the North Bridge from the window. She would be an influential intellectual figure in Emerson’s life, an independent scholar, and prolific letter writer herself.

Emerson was educated at Harvard, where he graduated at the exact middle of his class. He became a minister, got married, and was, sadly, widowed shortly after. This shook him to his core. He had come from a long line of ministers but no longer believed in acting the role of the religious go-between for people’s spiritual needs. He left his formal religious ministry in Boston in 1832 and, like many people pondering a life crisis and career switch, he traveled around

America and Europe. In October of 1834, his wanderings led him back to his origins, and he moved to the Old Manse in Concord, where his new life would begin.

He was living with his elderly step-grandfather, Ezra Ripley, as he began to write his first major work, Nature. Emerson put into words the idea that the divine can be found in the natural world and did not need the intervention of traditional religious ceremonies or appointed holy people. It would form the basis of thought behind the movement of Transcendentalism, and so the second Concord revolution would begin, on hallowed ground, in view of the base of the North Bridge.

Residence of Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1875

| All images courtesy of the Concord Free Public LibraryThe Emerson Residence

When he chose to establish his home with his second wife, Lidian, he bought the house called Bush in 1835, centrally located across the street from the building that now houses the Concord Museum.

The Transcendental Club began meeting in 1836, just as Nature was being published, and continued at various locations, including Emerson’s house, until 1840, when the members transitioned more into publication and formed the magazine The Dial to join their thoughts together in print. Emerson hired Margaret Fuller (1810-1850) to edit the magazine, although she was never paid for her work.

He would soon get to know the locals, including an eager young Harvard graduate who was well on his way to becoming a Townie. Emerson asked him if he kept a journal, and Henry David Thoreau would go on to write two million words in the journal alone, as well as several books and essays. Emerson’s presence attracted other intellectuals, including the Alcotts who moved to Concord in 1840 and Nathaniel Hawthorne, who took up residence at the Old Manse in 1842.

Emerson and Walden Woods

Even though Thoreau’s vision of Walden seems to be the one in the spotlight today, Emerson was key in granting him the use of the land and in preserving the land itself.

Emerson was in the habit of walking out to Walden once or twice a week and reading on its shore. He took inspiration for his early Transcendental writings from those walks. One day in 1844, he ran into some men selling a parcel of land touching the shore. He bought 11 acres at $8.10 each, known as the Wyman Lot, and later bought another 41 acres across the Pond, including what is now known as Emerson’s Cliff.

Thoreau had initially wanted to build on Flint’s Pond for his experiment in living but was rejected by the owners. He then turned to his friend, the new landowner of a scenic spot by the shores of Walden, and history was made. Thoreau built a cabin on the shores of Walden, spent two years, two months, and two days there, and eventually wrote and published Walden.

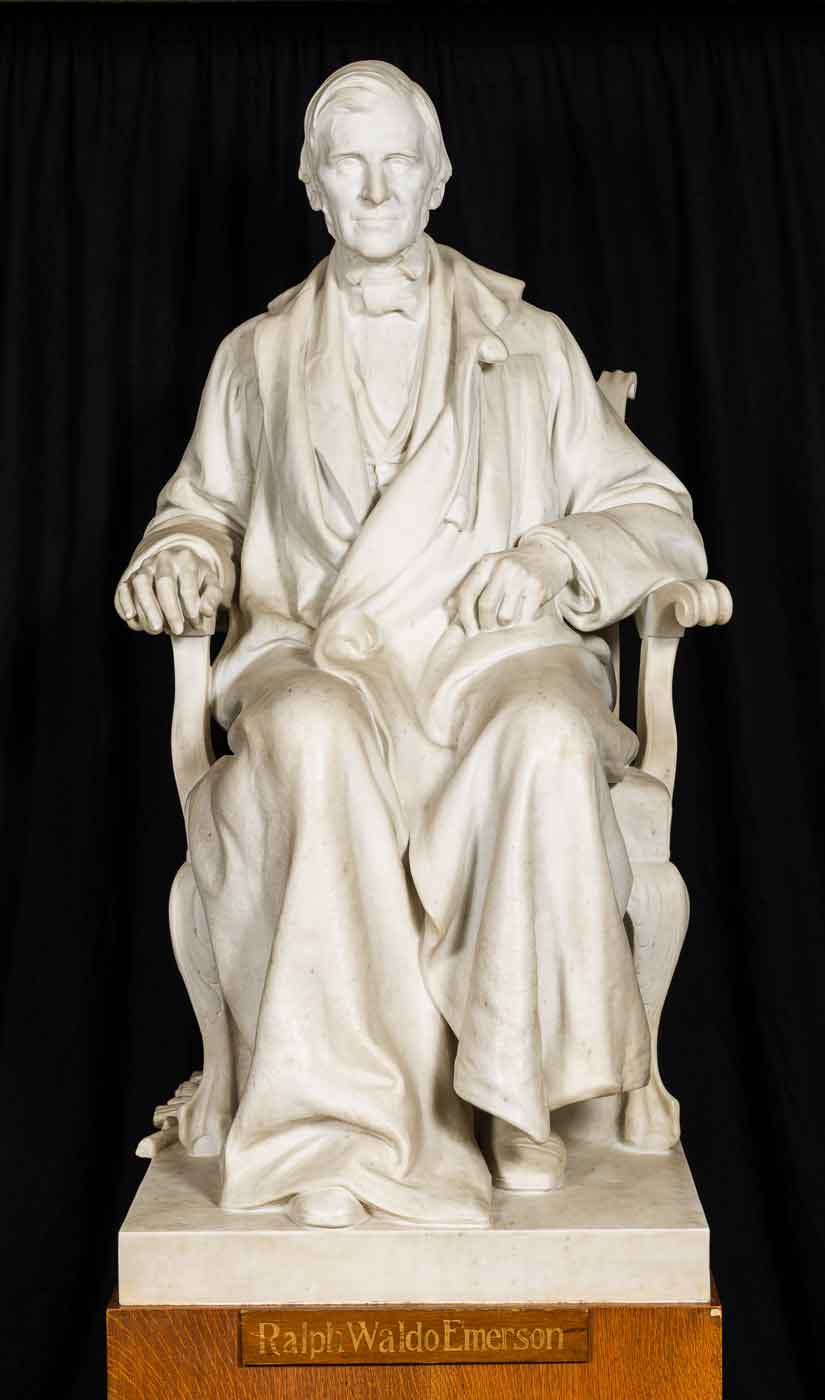

Sculpted by Daniel Chester French, 1914

| ©Jim Coutré PhotographyA BRIDGE TO THE FUTURE

Emerson was fêted in his lifetime and did what he could to support future generations and the young minds and talent in town. He would appear and/or offer the dedication address at all the town events, including the opening of Sleepy Hollow Cemetery (1855), the Concord Free Public Library (1873), and the Minute Man statue at the North Bridge (1875), which holds the words to his 1837 Concord Hymn on the pedestal. Today, we can see two sculptures of Emerson, both created by French, at the Concord Free Public Library. The bust, carved in 1883/1884 from an original model created in 1879, so impressed Emerson that he exclaimed, “Dan, that’s the face I shave!” But it is the other grander, seated statue that fully captures Emerson’s idealized persona, even though it wasn’t commissioned until after his death. Visiting this statue in the library lobby, one can see how it could be seen as the model for French’s later, best-known work, the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. Unveiled in 1914, the sculpture of Emerson happily haunts the Concord Free Public Library to this day, reminding the living of his influence on the freedom of thought.

FOR FURTHER READING

Baker, Carlos. Emerson among the Eccentrics: A Group Portrait. Penguin Books, 1997.

Cramer, Jeffrey S. Solid Seasons: The Friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Counterpoint, 2020.

Hall, Robert C.W. “Em_con_49 -- Herbert Wendell Gleason. Walden from Emerson’s Cliff.: Special Collections: Concord Free Public Library.” Em_Con_49 -- Herbert Wendell Gleason. Walden from Emerson’s Cliff. | Special Collections | Concord Free Public Library, concordlibrary.org/special-collections

Maynard, W. Barksdale. “Emerson’s ‘Wyman Lot’: Forgotten Context for Thoreau’s House at Walden.” The Concord Saunterer, vol. 12/13, The Thoreau Society, Inc, 2004, pp. 59–84, jstor.org/stable/23395273

Wilson, Leslie Perrin. “Emerson Statue Celebration: Special Collections: Concord Free Public Library.” Emerson Statue Celebration | Special Collections | Concord Free Public Library, 16 May 2014, concordlibrary.org/special-collections