public domain

public domainIn 1883, Lidian Emerson, widow of Ralph Waldo Emerson, hosted a gathering in her Concord home for Sarah Winnemucca, a Native American woman whose book Life Among the Piutes, Their Wrongs and Claims had recently been published. Mrs. Emerson and her friends were stalwart campaigners for human rights, and Sarah was on a mission to win justice for her people. This was just the kind of gathering that might help Sarah’s cause.

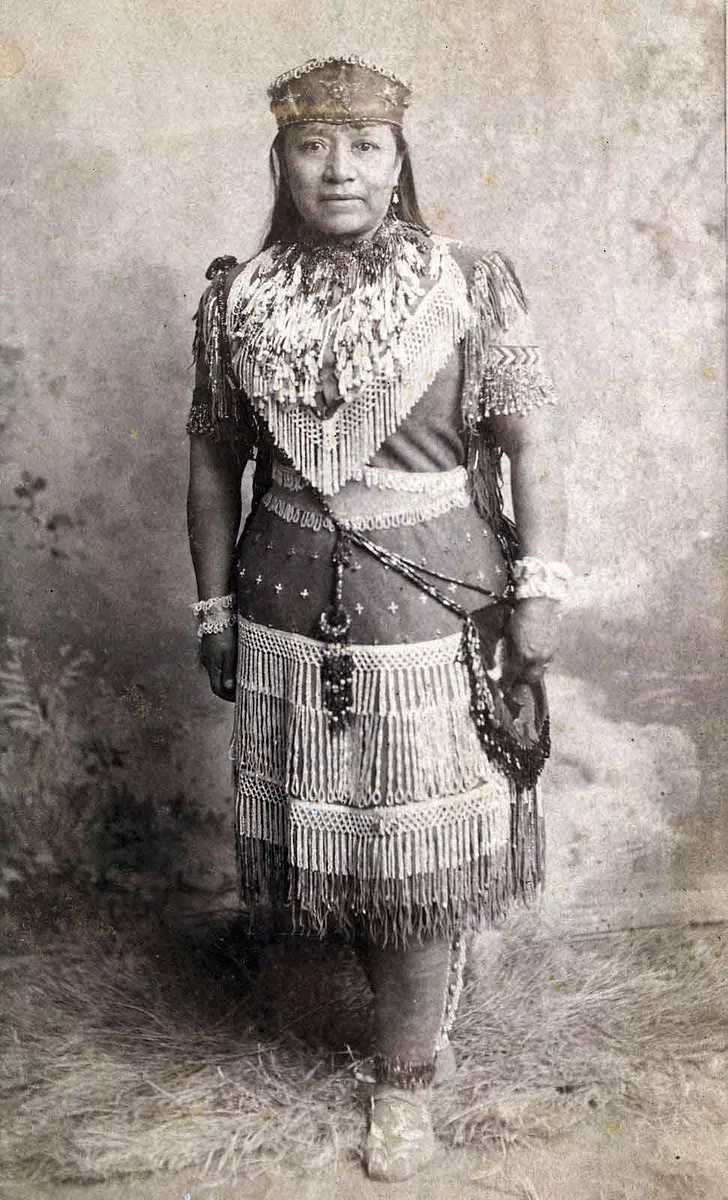

Throughout much of 1883, Sarah had been living in Boston at the home of Elizabeth Peabody and Mary Peabody Mann. Her homeland, though, was near Pyramid Lake in the northwestern part of Nevada. Sarah’s grandfather, Truckee, and her father, Winnemucca, were well-known leaders of the Northern Paiutes.* Sarah’s Paiute name was Thocmetony (“Shell Flower”), but to white people she was Sarah Winnemucca—or sometimes “Princess Sarah.”

Sarah had come East on a lecture tour seeking supporters. The U.S. government had forcibly relocated her people, and she was determined to help them regain the right to live on at least some portion of their own land. Her performances on stage were riveting and heart rending, but it was impossible in a single lecture to fully explain the wrongs her people had suffered. She wanted to write a book that would tell her story more fully, and the elderly Peabody sisters encouraged her to do so.

Mary Peabody Mann

Both Elizabeth and Mary had extensive experience

in editing, writing, and publishing, and their expertise would be essential to this project. Sarah had learned English while young, but, as an Indian, she had been denied formal schooling. Her extemporaneous speaking was impressive, but spelling was, as Mary put it, “an unknown quantity to her.” Sarah wrote down the stories she had been telling from the lecture stage, while Mary corrected the orthography.

Now that the book was in print, Peabody and Mann were making every effort to bring Sarah’s compelling story to their reform-minded friends and to circulate a petition urging the U.S. government to rectify some of the wrongs done to the Paiutes. The sisters knew that Sarah’s cause would find a sympathetic audience in Concord. As far back as 1838, more than 200 Concord women had signed a petition protesting the forced removal of the Cherokee from their traditional homelands.

Peabody and Mann had deep connections to Concord themselves. The two of them had made a home there together, along with Mary’s sons, after the 1859 death of Mary’s husband Horace Mann. Their sister Sophia also lived in Concord during the 1860s with her husband Nathaniel Hawthorne and their children. Elizabeth’s connection to the town went back even earlier. Her friendship with Ralph Waldo Emerson began when they studied Greek together in their teens and continued through his move to Concord and his marriage to Lidian.

Elizabeth Peabody

| Author unknown, Public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsAt the time of the Emerson marriage, Elizabeth was working as a teacher in Bronson Alcott’s Temple School in Boston. Her 1835 book Record of a School, which documented Alcott’s teaching methods, not only made Alcott famous, but became an opening salvo of the movement known as Transcendentalism. Elizabeth Peabody remained a central figure in that movement, best known for promoting other people’s careers. She had an extraordinary talent for lifting up others.

Peabody and Mann were both dedicated to educational reform. A book they co-authored in 1863 highlighted the importance of play and of time outdoors in nature. During her time with them, Sarah became almost like another sister. Like Elizabeth, Sarah was a gifted linguist. She spoke English and Spanish in addition to three indigenous languages, and she firmly believed in the power of education to bring intercultural understanding. Her descriptions of how Paiute children were raised bore a remarkable similarity to the educational ideas promoted by Peabody and Mann. Convinced that the two cultures had much to learn from each other, Mary wrote: “[W]hen something like a human communication is established between the Indians and whites, it may prove a fair exchange, and the knowledge of nature which has accumulated...may enrich our early education as much as reading and writing will enrich theirs.”

This was a radical idea at the time, and one that was heartily rejected by American policymakers.

After the publication of her book, Sarah Winnemucca continued lecturing to large audiences. She traveled to Washington, D.C. where her petitions with hundreds of signatures were delivered to Congress, and she testified movingly before the House Subcommittee on Indian Affairs. At last, when it seemed she had done all she could, she headed back to Nevada to realize her dream of establishing a school for Paiute children.

Statue of Sarah Winnemucca at the Capitol Visitors’ Center, Washington, D.C.

Despite immense obstacles, she managed to open a bilingual school, which she called the Peabody Institute. Even though the children at her school were clearly thriving under her tutelage, opposition to the school was unrelenting. Government policies of the 1880s were committed to establishing boarding schools far from the children’s families, where Indian children would be “Americanized” by losing all contact with their own language and culture.

Elizabeth Peabody stood in fierce opposition to such policies. After Mary’s death in 1887, Elizabeth’s devotion to Sarah’s exemplary school continued unabated. She met with government officials, wrote newspaper articles, and sent what aid she could—but white opposition, financial difficulties, and Sarah’s failing health brought the school to an end in 1889.

Sarah Winnemucca’s Indian school in Nevada was doomed to failure by the prejudices of her time, yet Elizabeth Peabody never regretted devoting the final years of her life to Sarah’s cause. Recalling his aunt, Julian Hawthorne wrote, “The last time I saw her was on the threshold of a little hut in Concord; she stood in her wrapper, her soft gray hair floating down her back, her face seraphic with holy purpose. As I turned at the gate, she threw up her right arm and called out, ‘I am the champion of the Indians.’ She said it half laughingly, for she was never deficient in the sense of humor; but she meant it.”

*Paiute is the spelling used now rather than Piute, as in Sarah’s book.