In 1859, militiamen were a common sight in Concord, having had a presence in the town for over two centuries. Uncommon, however, was the entirety of the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia descending on the town in early September 1859. Unlike April 19, 1775, the last time the militia flocked to Concord, this was not for a fight. Rather, militiamen were brought together to test and demonstrate their preparedness in the face of a potential rebellion that the political and military leaders of Massachusetts feared was inevitable. Choosing Concord was no accident either. While militia leaders would use this opportunity to inspect the readiness of their soldiers, doing so here at the flashpoint of the American Revolution was meant to remind these militiamen of the historical importance of their predecessors in securing a nation and that they might just be called on to do the same.

By the 1850s, the Massachusetts militia looked very different from the militia of 1775. Starting in 1840, the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia was established, which, as the name suggests, was made up of all volunteers. Every man 16 to 60 continued to nominally be in the “enrolled” militia, but in reality, the core of over 5,000 all-volunteer militiamen made up the backbone of the Commonwealth’s armed forces. These men trained regularly and were organized into companies with regiments, brigades, and divisions making up the succeeding levels of command. Already a highly sophisticated army, soldiers here were no stranger to encampments carried out at the regimental or brigade level, but never before (in Massachusetts or anywhere else in the nation) had a statewide encampment been conducted.

First proposed back in 1853, rising political and factional tensions over the 1850s encouraged the necessity of an encampment of this scale so militia discipline and equipment could be inspected and competency of leadership at various levels evaluated. In April of 1859, the general officers of Massachusetts set out to find a suitable location to host a force this size. Before long, Concord was chosen, not only for its central location in the state but also due to its historic association with the start of the American Revolution. The generals chose Loring’s Crossing, an unoccupied piece of land bordered on three sides by the Assabet River, Nashoba Brook, and Warner’s Pond. Here Camp Massachusetts was established and preparations to host the entirety of the volunteer militia for the 3-day encampment were made.

Militiamen trekked from all corners of the Commonwealth to Concord and reported for duty at Camp Massachusetts by the early morning of September 7, 1859. Following a dinner of roast beef at 12:30 p.m., the militia organized by division and started their ceremonial march in a column over two miles long to the site of the Old North Bridge. Though the bridge had since been torn down, the 1836 Battle Monument stood tall and served as a rallying point for the militia. Gathered at the monument, the militia gave three cheers to the minutemen of 1775 and the band played “Hail Columbia” and “Yankee Doodle.” They then circled back to finish their seven-mile trek and return to Camp Massachusetts for some much-needed rest.

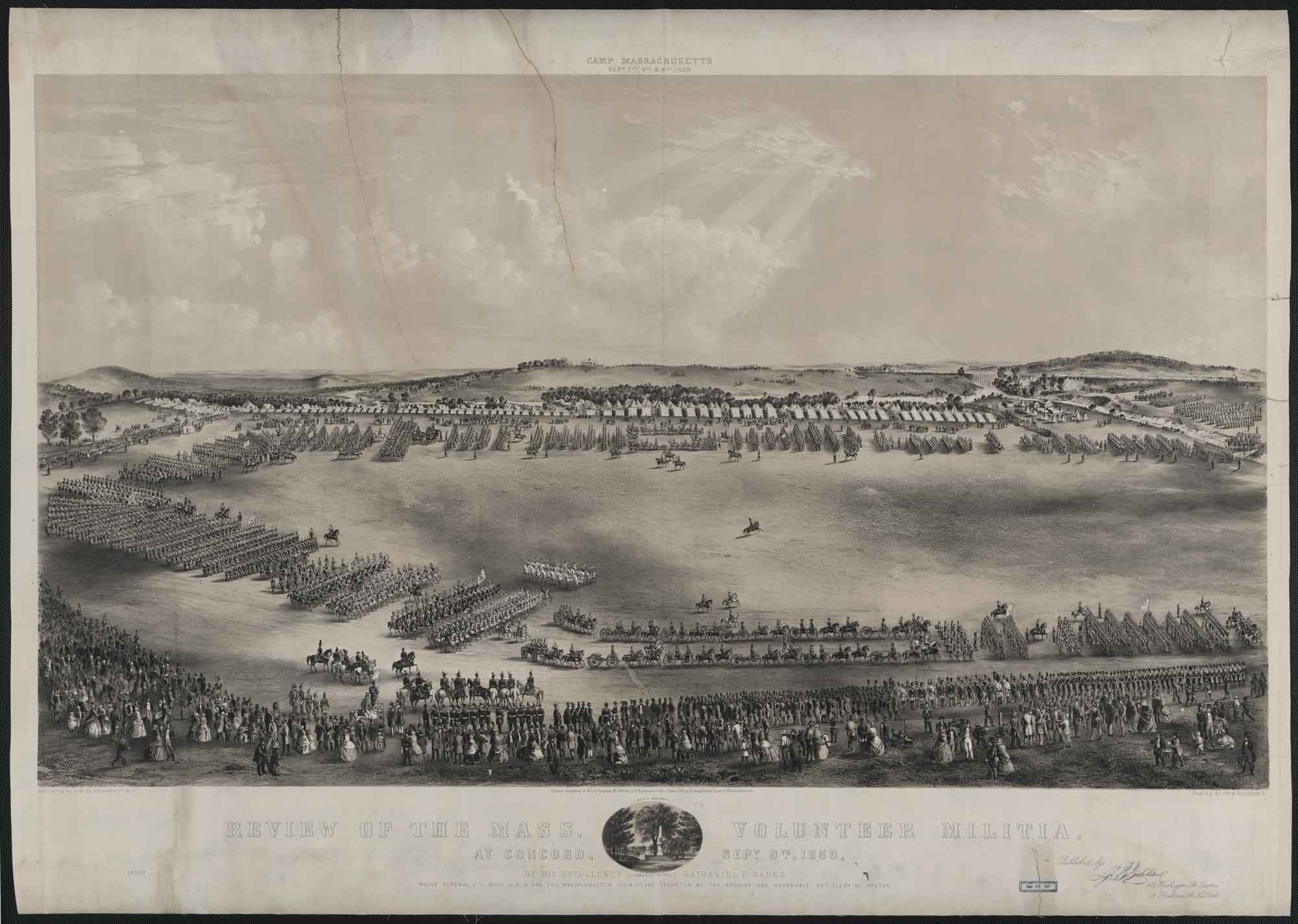

Review of the Mass. volunteer militia, at Concord, Sept. 9, 1859, by His Excellency (Commander-in-Chief) Nathaniel P. Banks

| © Library of CongressWith over 5,000 soldiers present and curious local spectators taking an interest in the encampment, militia leaders put in place several restrictions to preemptively cut down on rowdiness. First, only uniformed persons were allowed in the camp, and, likewise, soldiers were restricted from going into town. If a soldier was found sneaking out of camp, all traveling expenses that the state promised to cover for them would not be reimbursed. Additionally, absolutely no alcohol was allowed within the camp. Over the entire period of the encampment, there were 11 reported arrests of soldiers, with all but one being released soon thereafter. The state was exceedingly happy with these numbers in their official reports.

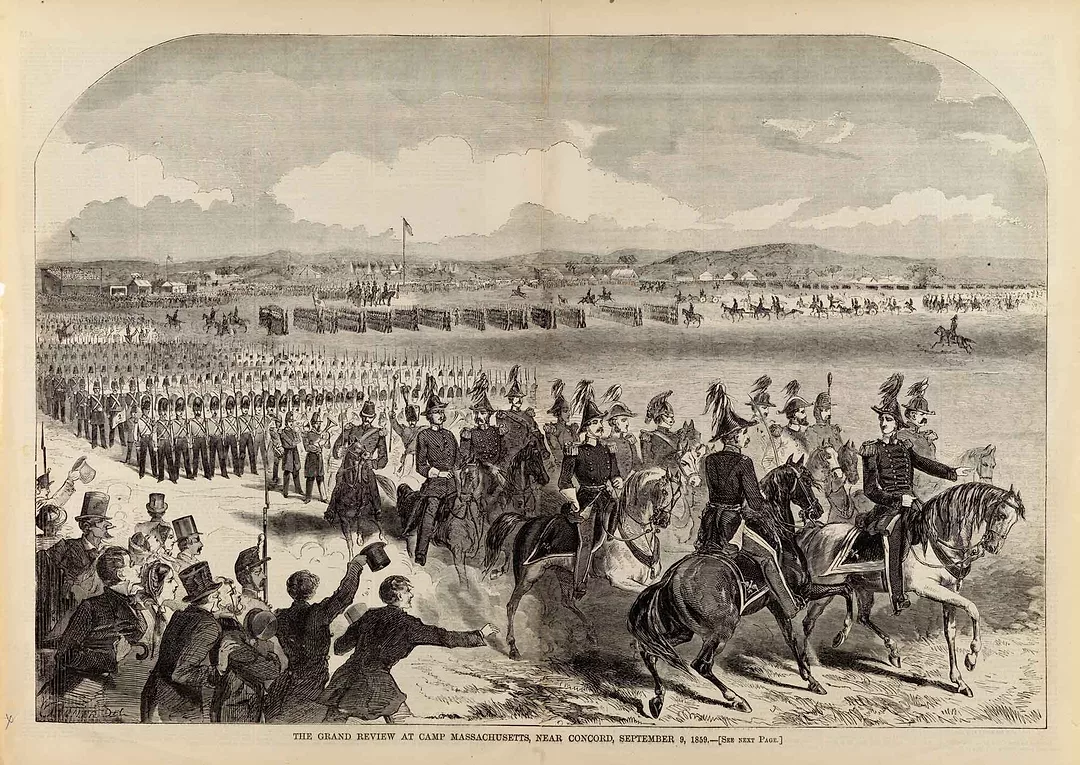

Day two began with reveille at 5:30 am and roll call soon thereafter. Breakfast was then followed by a long day of drilling for the soldiers. With numerous spectators present, brigadier generals observed battalion-level drills throughout the morning. This was followed by brigade drills where the previously observing brigadier generals were now being inspected by the major generals of the Commonwealth. Finally, Commander-in-Chief, Governor Nathaniel P. Banks, conducted his first review of the divisions led by his major generals. Along with Governor Banks was special guest US Army Major-General John E. Wool, a nearly 50-year army veteran who was brought to provide recommendations to the state militia based on his observations.

The review completed, the state’s 18 militia bands put on a concert that evening that not only included familiar American tunes such as “Hail to the Chief” and “Star Spangled Banner” but foreign songs like “God Save the Queen” and “German Fatherland.” The next day, Governor Banks and Major-General Wool conducted a final review, but this time they were accompanied by 50,000 spectators including governors and officers from Rhode Island and New Hampshire.

At the close of the review, Governor Banks spoke on the merits and importance of citizen soldiery and its necessity to the maintenance of a free government. He would end his speech equal parts reflective and prophetic: “Remember, soldiers, that here was the first blood of the Revolution shed, and I do not doubt that if you are ever called on to defend the country and its interests, you will be ready at a moment’s call.”

In response, the over 5,000 soldiers shouted, “We will!”

This call would occur sooner rather than later. In less than two years, South Carolinian rebels bombarded US Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Massachusetts’ response was overwhelming with five regiments answering Lincoln’s call for troops mere days after the attack. By months’ end, Massachusetts men had already shed blood at Baltimore and were poised to defend the Capitol against Confederate rebels. The encampment made this swift action possible as it demonstrated weak points in militia leadership and deficiencies in equipment that were handled over the following year. These Massachusetts soldiers, prepared and inspired by the 1859 encampment, would forever after be known as the minutemen of 1861 and heirs to their 1775 predecessors.