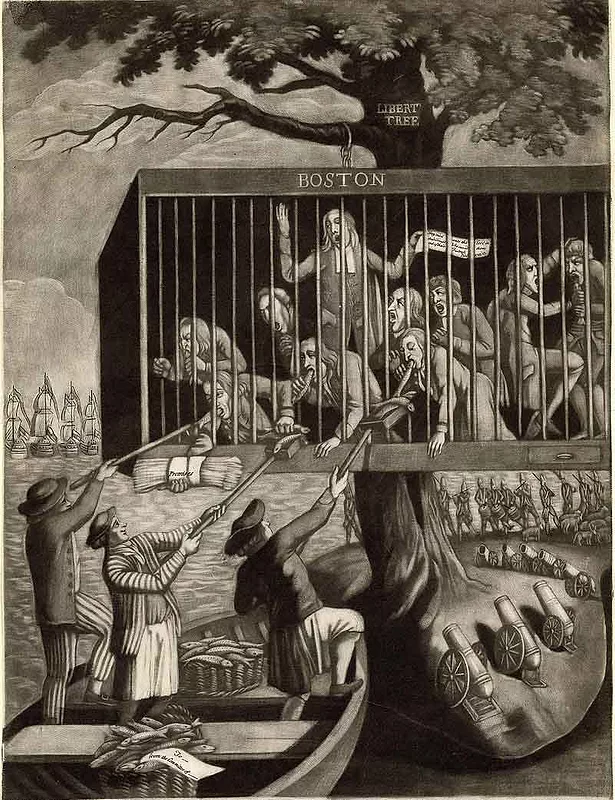

Passed on March 31, 1774, the Boston Port Act closed Boston Harbor to most commerce, demanded reparations for the destroyed tea, and imposed a naval blockade on the town. This drastic measure crippled the town’s economy—a significant blow to a seaport heavily reliant on maritime trade. Businesses shuttered, unemployment soared, and the town faced economic ruin.

Parliament believed that the colonies would not support Boston and that it would only be a short time before Boston acquiesced and paid for the tea, reestablishing British authority in the colonies.1 Word of the act reached the colonies on May 11, setting off immediate anger and opposition. The May 16 edition of the Boston Evening Post warned, “AMERICANS … Tyranny without a covering now stares you all in the face. . . You must ALL unite to guard your Rights, or you will ALL be slaves!”2

To the citizens of Massachusetts, it was clear that the British government had thrown down the gauntlet. A common belief quickly emerged that an immoral British government, having exhausted opportunities for plunder and profit in England, India, and Ireland, was now seeking a dispute with the American colonies as an excuse to enslave and deprive them of their wealth and liberties. Parliament had hoped to accomplish this goal quietly, but the furor aroused in the colonies by England’s previous economic policies had given the government a temporary setback. Now, mysterious men who controlled Parliament and the king’s ministers were secretly collaborating to incite a war openly, declare the colonists rebels, and enslave them. Passage of these “Intolerable Acts,” as they became known decades later, was seen as the most blatant of the attempts to provoke the coming war with her American colonies.3

News of the Boston Port Act spread rapidly throughout the colonies, sparking outrage and a surge of sympathy for the beleaguered town. Financial donations and material supplies, such as clothing and food, were quickly organized and delivered overland. Where Parliament had hoped to break Massachusetts of its defiance, the act was instead a rallying cry for unity among the colonies, fostering a shared grievance against British tyranny.

The response to the Port Act was swift and decisive. Throughout the colonies, correspondence committees toiled to spread a message of opposition and raise the alarm against a potential threat to their liberties. These committees were crucial in mobilizing public opinion and laying the groundwork for the First Continental Congress, a landmark gathering of colonial delegates charged with uniting the colonies against Crown policy.

Any hope of avoiding war now seemed dashed. In Boston, Brigadier General Hugh Earl Percy correctly surmised the state of affairs in Massachusetts on the eve of the American Revolution. “Things here are now drawing to a crisis every day. The people here openly oppose the New Acts ... In short, this country is now in an open state of rebellion.”4

Notes:

1 John C. Miller, Origins of the American Revolution (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1943), 359.

2 Boston Evening Post, May 16, 1774; Jared Peatman, “Coercion Gone Wrong: Colonial Response to the Boston Port Act,” The Gettysburg Historical Journal 1, no. 4 (2002).

3 For examples of this conspiratorial belief, see Declarations and Resolves, Town of Lexington, January 5, 1773, Lexington Town Hall, Lexington, Massachusetts. Transcribed copy in the possession of the author; Massachusetts Provincial Congress, Wednesday, October 5, 1774; Massachusetts Provincial Congress, The Journals of Each Provincial Congress of Massachusetts in 1774 and 1775, (New York Public Library, 1838).

4 Letter from Percy to the Duke of Northumberland, September 12, 1774; Hugh Percy, 2nd Duke of Northumberland, Letters of Hugh Earl Percy from Boston and New York, 1774-1776 (Boston, 1972).