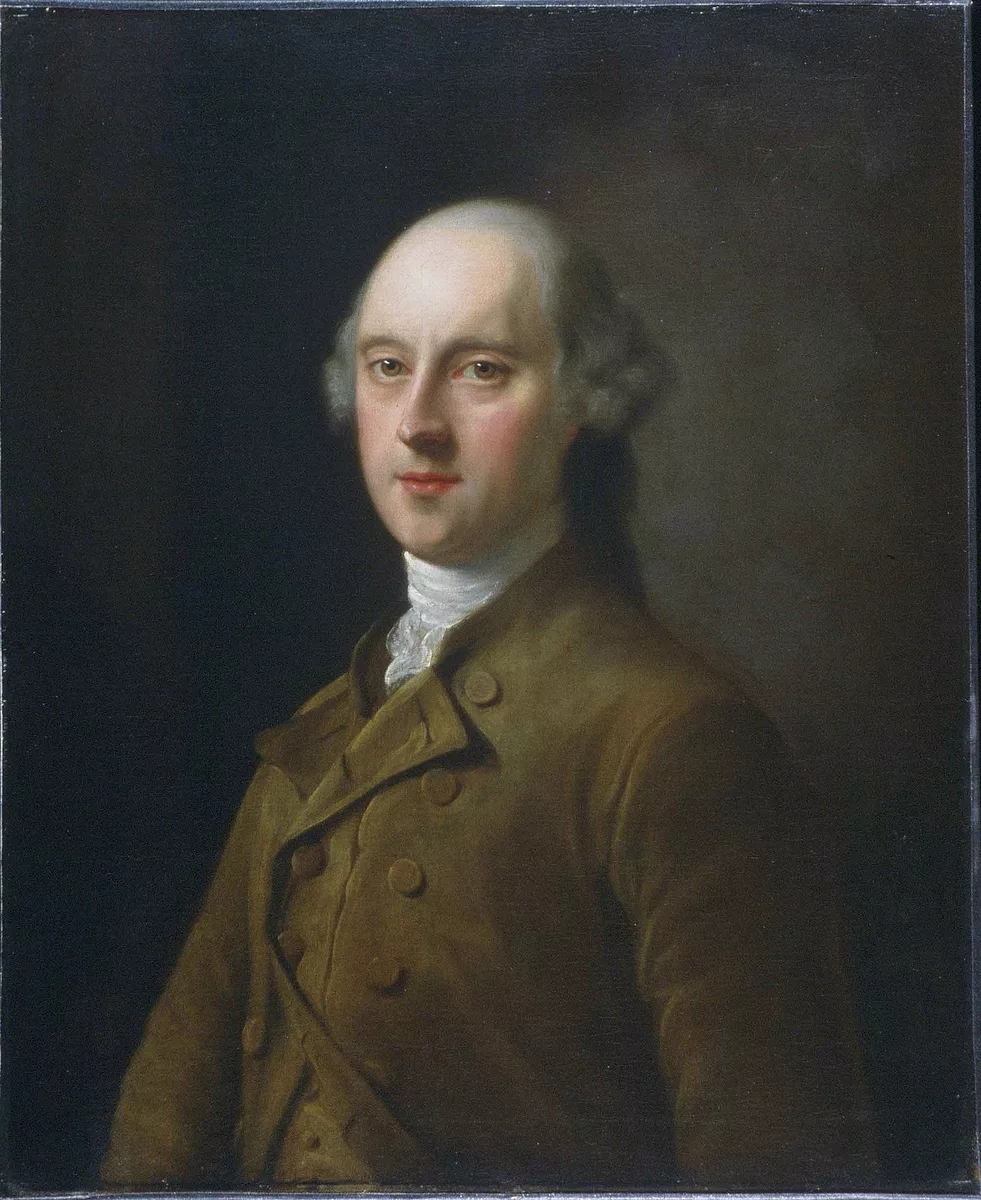

Perhaps one of the most underrated events of 1775 in Revolutionary America was the transmission of secret orders from William Legge, 2nd Earl of Dartmouth (1731-1801) and His Majesty’s Secretary of State for the American Department, to Gen. Thomas Gage, military governor of Massachusetts and commander of the British army in North America, to end the colonial insurgency by force if necessary. Dartmouth’s letter would appear to have considerable historical significance, as it provided the authorization for which Gage had been waiting in British-occupied Boston to execute his plans for dispatching a regiment into the Massachusetts countryside and thereby triggered the clashes at Lexington and Concord. Still, this correspondence has lingered in undeserved obscurity over the centuries, according to at least one modern-day study of how England’s policies led to armed rebellion by her New World subjects.1

Lord Dartmouth was actually regarded by many as sympathetic to the colonies—more so than his predecessor, the earl of Hillsborough—when his stepbrother and prime minister, Frederick, Lord North, named him secretary for America in 1772.2 Dartmouth assured Philadelphia’s Joseph Reed in mid-1774 that “there is not in any part of the king’s dominions a more real friend to the constitutional rights and liberties of America than myself,” and that “his regard [for] the colonies” would not dissipate unless there transpired “the clearest evidence of a determined contempt and disregard of the mother country.”3 Over the next six months, however, that evidence became apparent to His Lordship, as well as to George III and his other ministers.

Writing from Boston in March 1775, Maj. John Pitcairn anticipated a move by his fellow Redcoats against the insurrectionists presently, as orders were “anxiously expected from England to chastise those very bad people.” He remained confident that “one active campaign, a smart action, and burning two or three of their towns, will set everything to rights,” and that only military measures “will ever convince those foolish bad people that England is in earnest.”4 Pitcairn’s expectations were met when Dartmouth’s missive to Gage—drafted on January 27 in consultation with the king and North’s cabinet—arrived in Boston on April 14.5

The Dartmouth letter conveyed the collective opinion of decision-makers in London that in order to respond suitably to “the violences committed by those who have taken up arms in Massachusetts” and reestablish British authority there, “the essential step to be taken … would be to arrest and imprison the principal actors and abettors6 in the provincial congress, whose proceedings appear in every light to be acts of treason and rebellion.”7 Dartmouth advised that reinforcements were on the way and counseled resolution on Gage’s part: “The king’s dignity and the honor and safety of the empire require that in such a situation, force should be repelled by force.” In a final spur to action, the letter concluded by reminding Gage that a clause in the Massachusetts charter authorized the governor to declare martial law in the event of “war, invasion, or rebellion.” Accordingly, hostilities erupted five days later on April 19, igniting the longest military conflict in American history before Vietnam. As Thomas Jefferson’s words would augur independence for America, so William Legge’s words augured war for Great Britain.

NOTES

1 Nick Bunker, An Empire on the Edge: How Britain Came to Fight America (Alfred A. Knopf, 2014), 357. 2 Eric Robson, The American Revolution In its Political and Military Aspects, 1763-1783 (W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1966), 22; Andrew Jackson O’Shaughnessy, The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of the Empire (Yale University Press, 2014), 51. 3 Lord Dartmouth to Joseph Reed, July 11, 1774, in William B. Reed, Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed (Lindsay and Blakiston, 1847. Reprint: Adamant Media Corporation, 2006), 1:72-73. 4 John Pitcairn to the Earl of Sandwich, March 4, 1775, in The Spirit of ‘Seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution As Told by Participants, eds. Henry Steele Commager and Richard B. Morris (Harper & Row, Publishers, 1967), 62. 5 Dartmouth’s letter remained in his desk for weeks before being sent as events played out in Parliament. A copy was delivered to Gage in Boston by the Nautilus before the original arrived aboard the companion sloop Falcon. See Rick Atkinson, The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Concord, 1775-1777 (Henry Holt and Company, 2019), 51. 6 Although Dartmouth did not name them in his letter, it would have been understood that Samuel Adams and John Hancock were prime targets of His Majesty’s government among “the principal actors and abettors in the provincial congress.” See Walter R. Borneman, American Spring: Lexington, Concord, and the Road to Revolution (Little, Brown and Company, 2014), 115. 7 Dartmouth to Thomas Gage, January 27, 1775, in The Correspondence of General Thomas Gage with the Secretaries of State, and with the War Office and the Treasury, 1763-1775, ed. Clarence Edwin Carter (Yale University Press, 1931-33. Reprint: Archon Books, 1969), 2:179-183. It is noteworthy that Dartmouth’s letter left the timing and operational details of the actions he urged upon Gage to the latter’s discretion while making specific suggestions about troop dispositions and fortifications, and it has been suggested that this was done so that if Gage was able to quell the unrest, Dartmouth and the government in London could take credit for that success, but if Gage failed, the fault could be ascribed to his execution. See Borneman, American Spring, 115-116.