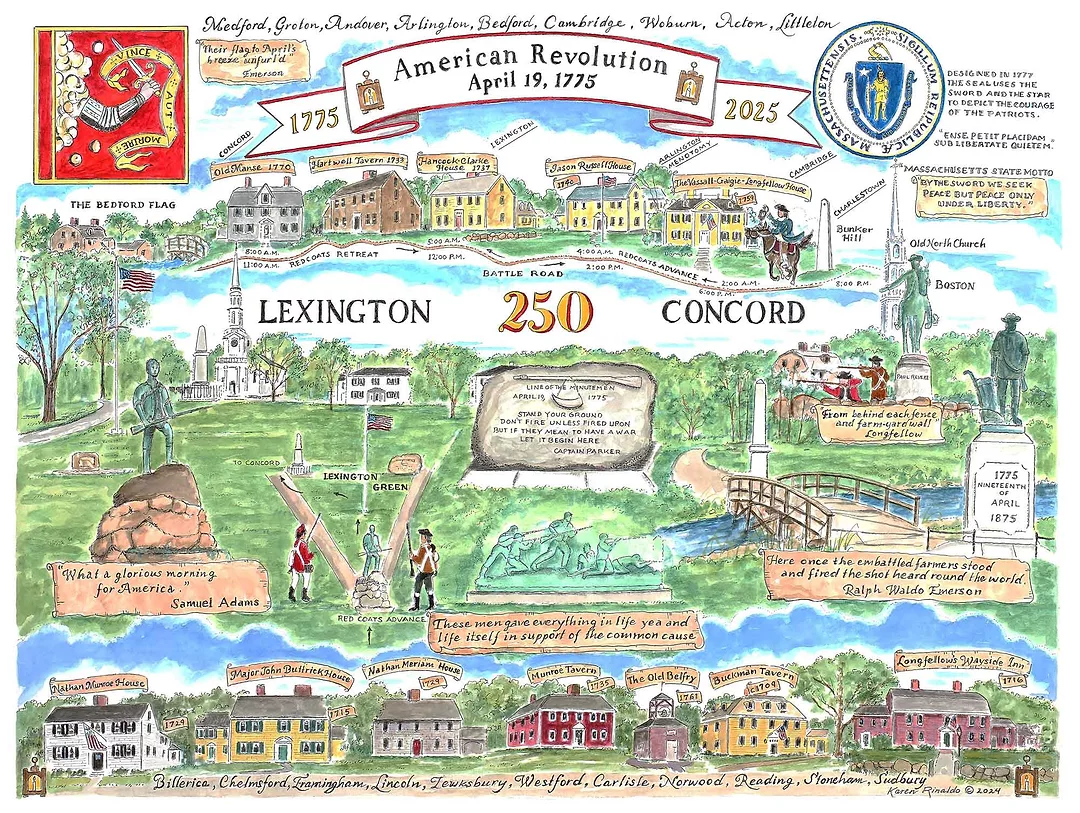

After telling the tale of The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow ended his epic poem with the words, “The rest you know from the books you have read.” But in case you haven’t read books about the battles at Lexington and Concord, Cape Cod artist Karen Rinaldo will sum it up for you in a single piece of art, currently on display at the Concord Museum.

The artwork starts in the upper right corner with Paul Revere seeing the flash of two lanterns hung in the Old North Church steeple in Boston on the night of April 18. He gallops along Massachusetts Avenue from Charlestown at about nine pm, through Menotomy (now called Arlington), and arrives in Lexington late on the night of April 18 to warn Samuel Adams and John Hancock that 700 British soldiers were coming to seize the munitions stored in Concord.

The alarm bell rings out across Lexington Green to alert the militia to muster. About 80 Lexington militiamen respond to face the British Regulars when they arrive at dawn on April 19. The painting records the movement of the Redcoats as some of them veer off the road to Concord to accost the colonists on Lexington Green and order them to disperse. Of course, they do not disperse. They maintain two ranks across the Green until a shot is fired; no one knows who shot first. As Hancock and Adams escape, Adams hears the musket fire and exclaims, “What a glorious morning for America!” The battle leaves eight militiamen dead and 10 more wounded, but there are no British casualties; those will happen in Concord.

As the minutemen look after their casualties, the Regulars form up and continue the march to Concord. The right side of the artwork illustrates what happens next. The Concord and Acton minutemen on the hill overlooking the North Bridge see smoke billowing from the town and, worried that the town is being burned, they advance down the hill to the bridge and exchange fire with the British, mortally wounding three. Although there had been clashes with colonists before, including the Boston Massacre in March 1770, this was the first time that the colonists had killed a soldier of the King.

The British begin their retreat; a 20-mile march back to Boston. Colonial militiamen on their way to Lexington hear reports of the morning encounters and stay to ambush the Regulars on their return march to Boston. Fighting as they had learned from the Wampanoags, the colonists shoot “from behind each fence and farmyard wall” as the Redcoats march down the middle of the road to their nighttime bivouac on Bunker Hill, the scene of their next clash eight weeks later.

The houses and buildings portrayed along the perimeter bore witness to the battle, and the towns listed around the edge were among the many New England towns that provided the thousands of militiamen who fought so courageously on that day. The War for Independence had begun!

The Skulking Way of War

My assessment that the colonists learned their fighting style from the Wampanoag is based on experience and research. As a retired Marine Corps colonel, I have taught battlefield tactics, emphasizing adaptability. As a co-author of “In the Wake of the Mayflower,” I explored the pilgrims’ first encounter with the Wampanoag who attacked the pilgrim explorers at dawn, accompanying their arrows with a loud shrieking sound to terrify the Englishmen. After a short skirmish (with no record of casualties on either side), the 30 Wampanoags vanished into the woods.In his book, The Skulking Way of War, Colonel Patrick Malone notes, “Everyone agreed by 1677 that warfare in New England forests required departures from conventional European methods.” Malone quotes John Eliot, the famous preacher in Natick who converted the “Praying Indians.” “In our first war with the Indians, God pleased to show us the vanity of our military skill, in managing our arms, after the European mode. Now we are glad to learn the skulking way of war.”

The final element that cemented my conclusion, was at the dedication of the Mashpee Wampanoag Veterans Garden in Mashpee Center, when Chief Flying Eagle pointed out to me that the Wampanoag Tribe had participated in every American battle from the Revolutionary War right up to Iraq and Afghanistan. The names of those killed in battle are proudly etched into the markers in the circle. Among the honorees are fifteen Wampanoag men who were killed while serving with the colonists in the American Revolution.

Thus, the colonists defeated the strongest army on earth by employing the lessons taught them by the Wampanoag fighters - the skulking way of war.