In 1860, Nathaniel Hawthorne and his family returned to Concord after living abroad for seven years. Hawthorne had been appointed the Consul to Liverpool, England, in 1853 after writing a campaign biography for his college pal Franklin Pierce, a biography that helped Pierce become the 14th president of the United States. Now, back in the home they called The Wayside, the Hawthornes would rejoin the circle of literary friends that included the Alcotts, who were living next door at Orchard House. Both homes are about a half a mile up Lexington Road from the home of Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry Thoreau lived across town on Main Street. They were all pleased to have the Hawthornes back; Bronson Alcott would report in his journal about a party in the Hawthornes’ honor: “Eat strawberries and cream at Emerson’s with Hawthorne, Thoreau, Sanborn, Hunt the artist, Keyes, and Cheney - a party made to welcome Hawthorne home to…Concord.”

Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1862

| Library of CongressThe homecoming was not entirely happy for the Hawthornes. Their oldest daughter, Una, had contracted malaria when they were visiting Italy in 1858 and had almost died. She was very ill for several months and would never fully recover, and she continued to experience physical and mental health issues after the family returned to Concord. Louisa Alcott would sadly remember Una as often being in a “high state of wrath and woe.”

The close-knit literary community would suffer a major loss with the death of Thoreau in May 1862, and again in May 1864 when Nathaniel Hawthorne would die at the age of 59. Hawthorne’s wife, Sophia, was given the news by her sister, Elizabeth Peabody, who had been informed by former President Pierce, who had been at Hawthorne’s side when he died in his sleep as the two friends traveled through New Hampshire. Sophia wrote about her husband’s death to her friend Annie Fields: “My darling has gone over that Sapphire sea, and these grand soft waves are messages from his Eternal Rest.”

Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, 1861

| Peabody Essex MuseumUna and her brother Julian made their father’s funeral arrangements – Sophia was too distraught to deal with it. Hawthorne was buried at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, with Emerson, Bronson Alcott, and Franklin Pierce among the pallbearers. Alcott noted the loss of both Thoreau and Hawthorne in his journal, sadly commenting on the “Fair figures one by one…fading from sight.”

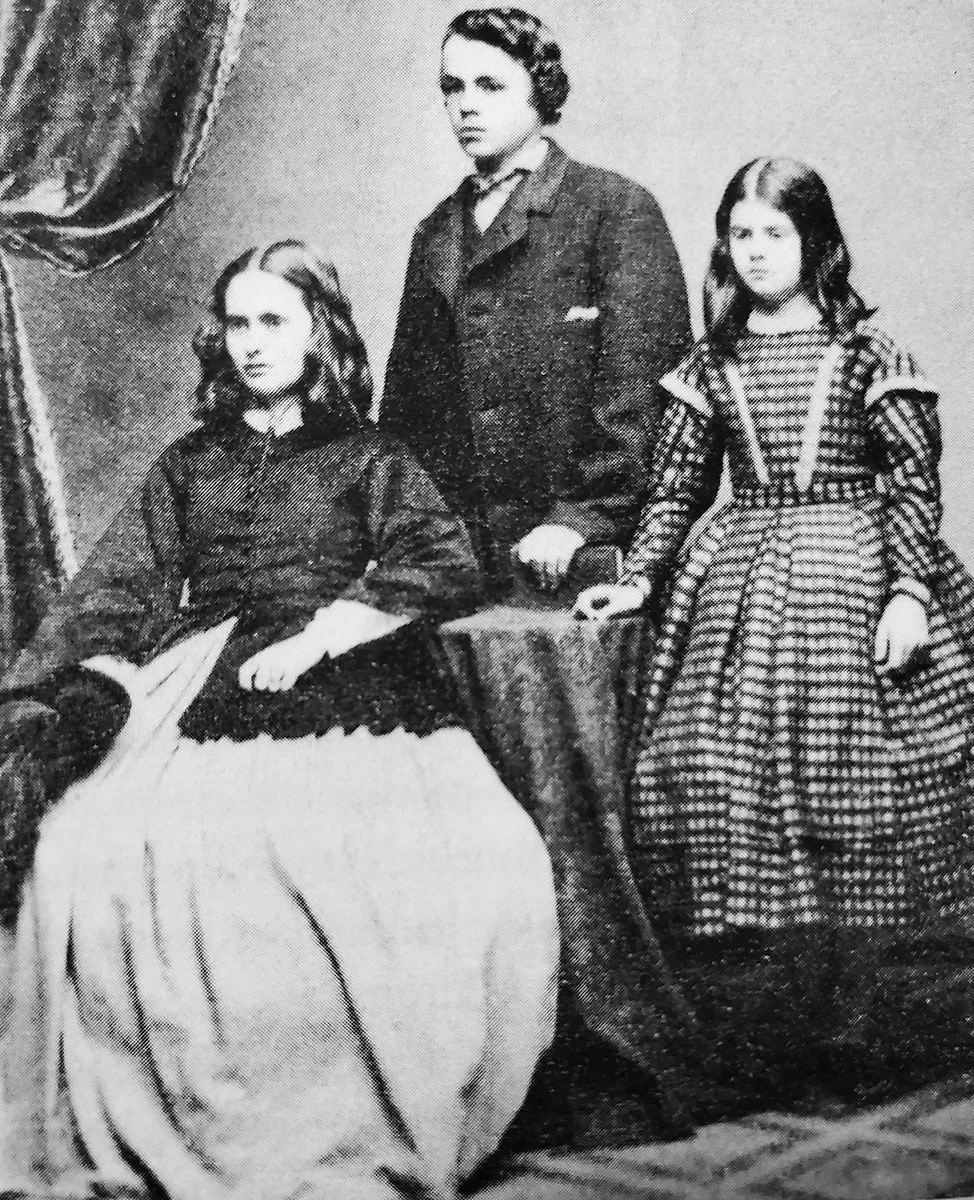

Sophia and her children continued to live at The Wayside, and Una, Julian, and Rose (all young adults by the late 1860s) continued to be a part of the literary community – in particular, they remained good friends with the Alcotts next door. Julian would remember “my two sisters and myself and the Alcott girls were in and out of one another’s houses all the time, almost forming one family.”

Una, Julian and Rose, 1861

| Peabody Essex MuseumHawthorne’s death left the family in dire financial straits. Sophia threatened to sue his publisher, James T. Fields, for not paying enough in royalties from Hawthorne’s book sales. Fields blamed his recently deceased business partner, William Ticknor, for the error, but claimed that no written contract between Hawthorne and Ticknor actually existed. Saying that she preferred “peace to pence” Sophia and Fields agreed to a financial compromise.

As Sophia battled constant health issues, she did her best to continue her husband’s literary legacy and earn a living for her family. She began editing Hawthorne’s notebooks, with the edited versions being serialized in the Atlantic Monthly. She published Hawthorne’s Passages from the American Note-books in 1868 before working on her own book, taking her own letters and journals from when the Hawthornes were in Europe, and publishing a successful travel book, Notes in England and Italy, in 1869.

None of the Hawthorne children ever had any sort of formal education. Their mother home-schooled them, instructing them in French, geography, and dancing lessons. Both parents insisted that none of their children should learn to read before they turned seven. Ellery Channing remembered them as being “raised in seclusion” by their loving (if over-protective) parents and having nothing but “bad manners” when he visited the Hawthornes in Lenox, Massachusetts, in 1851. Upon returning to Concord, Julian began attending the school of Frank Sanborn. Although the school was coeducational, Una and Rose did not attend; Sophia frowned on the idea, writing Sanborn: “We entirely disapprove of this commingling of youths and maidens at the electric age in school. I find no end of ill effect from it, and this is why I do not send Una and Rose to your school.” Private tutors would be hired to educate Una at The Wayside.

Julian entered Harvard College in 1863, but he did not graduate; it was during his freshman year that his father died, and Julian now considered himself head of the Hawthorne household - he was 17 years old. He quit Harvard and took over his father’s study in the tower of The Wayside. His mother recalled how the difficult time “made a man of him, for he feels all the care of me and his sisters.”

In 1866, Sophia sent 15-year-old Rose to a girls’ boarding school in nearby Lexington. With money being an issue, her schooling was paid for by family friend Mary Loring. Sophia wrote to her sister in 1868, “Rose is now in (school), and Mary Loring’s aid in this important matter has relieved me of a great anxiety and trouble. For Rose is hungry to learn and it seemed cruel not to give her a chance.” Rose did not enjoy her boarding school experience.

In 1867, Una was briefly engaged to Storrow Higginson, the nephew of Thomas Wentworth Higginson; Wentworth and Una became particularly close, and Una even took to calling Higginson “Uncle Wentworth.” He described an 1867 visit to The Wayside that gives a very compelling description of life in the Hawthorne family: “[Una’s] face and eyes were what I expected…and her magnificent hair blazed and glittered upon me in the doorway most unexpectedly...She was sweet and confiding as possible…Mrs. Hawthorne asked [Rose] to sing to us and she sang dreamy and thoughtful songs. ‘It is not singing, it is eloquence,’ said the proud and loving mother…I watched her as she sat on her low chair by the fire, while the music lasted; her hair was white, her cheeks pallid, and her eyes full of tender and tremulous light…In the evening I sat and looked over some of Hawthorne’s note-books, perhaps in the very chair where he had sat, looking up sometimes at the quiet face of the gray-haired woman he had loved or the bright heads of his young daughters. Una sat by the stove, in her expressive quietness, while little Rose shifted uneasily from one book to another…”

Portrait of Una is taken from a tintype owned by Thomas Wentworth Higginson, 1868.

| Public domainThe relationship between Una and Storrow Higginson is shrouded in mystery. He proposed to Una on the last day of April 1867, telling her that he was “hopelessly in love with her” – and she “fainted dead away” at the proposal. After turning Storrow down she eventually changed her mind and said yes. But they would never marry; for reasons that are still unknown, Una called off the engagement the next year.

In 1868, Sophia and the children moved to Dresden, Germany. Family finances played an important role in the move: Elizabeth Peabody had recently visited Dresden and recommended it as an affordable place to live. Julian’s education also helped in the decision. He was pursuing an engineering degree, and Germany offered affordable opportunities for his education. But the Hawthornes’ time in Germany would be short-lived; the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 forced them to leave Germany and settle in London, England.

After Nathaniel Hawthorne’s death, his family went through a tough transition, facing financial, physical, and emotional challenges. Sophia and Una would never recover their health. Julian had moderate success as a writer, but his later years were plagued by scandal. After an unsuccessful marriage, Rose would become a Catholic nun. But throughout their lives the shadow of their father seemed to hover over them – being a Hawthorne was often a blessing, sometimes a curse. But for all of them life was never the same after they lost Dear Papa.