When November rolls around each year many Americans begin to think about the upcoming holidays. Traditional family recipes are dusted off for Thanksgiving as relatives and friends are invited to share the feast. Almost as soon as dinner is over, thoughts turn to Christmas as decorations, presents, and parties become the center of attention. Many of our holiday traditions date back to the 19th century, and modern Americans would easily recognize their ancestor’s Thanksgiving and Christmas celebrations.

As the Puritan hold on New England weakened by the 19th century, holiday celebrations became more popular, and it was Thanksgiving and New Year’s Day when family and friends would gather for celebrations. Our modern Thanksgiving holiday began to take shape in the mid-19th century, with President Lincoln making it a national holiday in 1863. An 1865 Thanksgiving was not much different from our own today.

Celebrating the new year was a major holiday for many New Englanders. To modern eyes, New Year’s Day in the 19th century would look much like our Christmas; house parties would include songs and a large buffet with eggnog and sweet treats, while small presents would be exchanged amongst friends and family.

Nathaniel Hawthorne reading to his family at The Wayside, 1864. From A Pictorial History of American Literature by Van Wyck Brooks and Otto Bettmann. Published by J. M. Dent and Sons Ltd., 1956.

| Public domainBy the 1840s, the celebration of Christmas was becoming more acceptable throughout New England, but it wasn’t always that way. The early Puritans who settled in Massachusetts considered the holiday to be unnecessary, a distraction from their strict religious discipline. In 1659, Massachusetts made it a crime to observe Christmas in any way other than attending church. That law was repealed in 1681, but Christmas was still unpopular in Massachusetts.

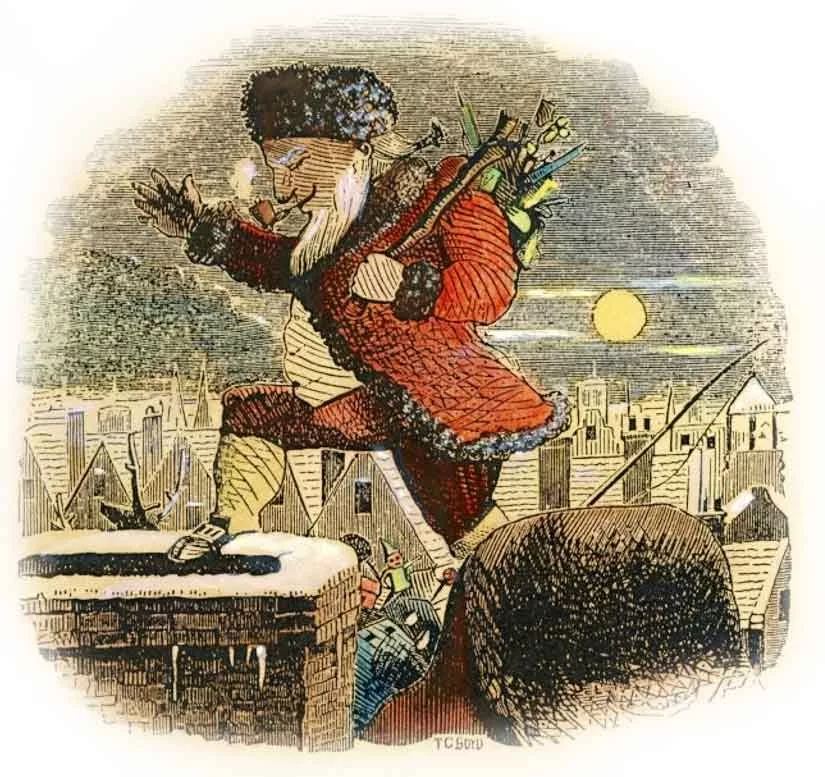

The influx of German and Irish immigrants in the mid-19th century saw Christmas celebrations becoming more common, even among native-born Yankees, so much so that in 1856 Massachusetts made Christmas a legal holiday. For many New Englanders it was a secular holiday rather than religious. Stores and shops quickly caught on to the growing popularity of Christmas and by the 1830s book publishers were producing fancy and expensive “gift books” by popular writers like Charles Dickens specifically for Christmas. And merchants were using the image of Santa Claus in advertising to entice gift giving.

New Year’s Eve 1865. Lithograph By Fuchs. Published By Kimmel and Forster; 1865.

| Public domainOf all the Concord writers, the one who is best associated with Christmas is Louisa May Alcott; after all, her most famous book begins with the line, “Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents.” As early as the 1840s, the always-progressive Alcott family celebrated the holiday when few New Englanders did. In his Fruitlands Journal from 1843–1844, Bronson Alcott wrote about exchanging “little gifts” with his children on Christmas Day. And in December 1846 the Emersons rode to the Alcott’s Hillside in a horse-drawn sleigh to enjoy a festive Christmas dinner that included individual notes tucked away inside pies.

It seems that the Emersons themselves did not celebrate Christmas, and they typically exchanged gifts on New Year’s Day. Like many of us, Waldo had a hard time deciding on what sort of gifts to buy, writing in 1844, “If at any time it comes into my head that a present is due…I am puzzled what to give, until the opportunity is gone.” It should be no surprise that he favored books as a gift, but he added, “Flowers and fruits are always fit presents; flowers, because they are a proud assertion that a ray of beauty outvalues all the utilities of the world.”

In later years, after she achieved success as an author, Louisa Alcott wrote dozens of Christmas stories. One of her favorite books as a young girl was A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, and Louisa’s stories show Dickens’ influence as she wrote about the true meaning of Christmas and how it is better to give than to receive - a belief she learned from her father and mother.

In December 1854, Louisa’s first book was published. Called Flower Fables, it was a collection of stories that she had created for the young Ellen Emerson. Fifteen-year-old Ellen would write of a very special present that she received that holiday season: “So this morning I saw a bundle on the entry directed to me. I opened it and found the ‘Flower Fables’ all bound and printed very nicely with pictures, but on turning it over I saw my name in large letters and discovered that ‘twas dedicated to me! Of course, I fell down in a swoon…”

Stories about the Thoreau family celebration are hard to come by. Henry Thoreau barely mentions any holiday in his Journal, and it’s not known exactly if - or how - the Thoreaus celebrated any holiday. But we do have a brief glimpse into a Thoreau Christmas when Henry and his siblings were small children, and it comes from his older brother John. Jr. in an 1839 letter to a friend:

“When I was a little boy I was told to hang my clean stocking with those of my brother and sister in the chimney corner the night before Christmas, and that ‘Santa Claus,’ a very good sort of sprite, who rode about in the air upon a broomstick…would come down the chimney in the night, and fill our stockings if we had been good children, with dough-nuts, sugar plums and all sorts of nice things; but if we had been naughty we found in the stocking only a rotten potato, a letter and a rod. I got the rotten potato once, had the letter read to me, and was very glad that the rod put into the stocking was too short to be used.”

The first published American illustration of a Christmas tree. Printed in Boston, 1836.

| Public domainConcord was extremely progressive when it came to celebrating Christmas. In 1853, Caroline Brooks Hoar came up with the then-novel idea of a town-wide celebration of the holiday. The festivities would be held at the Concord Town Hall, and every child in town (up to the age of 16) would get a present. And while there is no evidence that Henry Thoreau celebrated the holiday, he agreed to supply a tree for the festival:

“Got a white spruce for a Christmas-tree for the town out of the spruce swamp opposite J. Farmer’s. It is remarkable how few inhabitants of Concord can tell a spruce from a fir and probably not two a white from a black spruce, unless they are together.”

Two days later he would report in his Journal:

“In the town hall this evening, my white spruce tree...looked double its size and its top had been cut off for want of room. It was lit with candles, but the star-lit sky is far more splendid tonight...”

The idea of a whole town celebrating Christmas was still such a rarity in New England that the Springfield [Massachusetts] Republican newspaper published a story about Concord’s “interesting festival.” “All the children of the town participated,” the newspaper reported, and someone dressed as St. Nicholas distributed presents to the children - some 700 in all!

Even Thoreau wasn’t immune to the idea that a new year can bring new hopes and dreams. In 1852, he wrote in his journal, “Woe be to us when we cease to form new resolutions on the opening of a new year!” Six years later he was still ruminating on the meaning of a new year and - not surprisingly - its connection to nature: “Each new year is a surprise to us. We find that we had virtually forgotten the note of each bird, and when we hear it again it is remembered like a dream, reminding us of a previous state of existence…The voice of nature is always encouraging.”

Many of the holiday traditions that the Concord writers were familiar with are still in vogue, as are the reasons behind these celebrations - peace, love, hope, and joy. Emerson called it a season for “tokens of compliment and love” while in December 1854, Nathaniel Hawthorne reflected on sentiments we can still relate to every holiday season:

“I think I have been happier this Christmas than ever before, — by my own fireside, and with my wife and children about me, — more content to enjoy what I have, — less anxious for anything beyond it in this life.”