“Is it true that Emerson is going to take a gun?” asked Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. “Then I shall not go, somebody will be shot.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson was no marksman, but in July 1858, he bought a “rifle & gun” (a two-barreled rifle-shotgun combination) for twenty-five dollars, prompting his friend Henry David Thoreau to quip, “The story on the Mill Dam is that he has taken a gun which throws shot from one end and ball from the other.”1

What inspired the gentle Sage of Concord to acquire this unlikely weapon? He was gearing up for a trip to the Adirondack Mountains, where some of the leading intellectuals of antebellum America were planning to spend a week or two roughing it in the woods. In the event, no one was shot, and this brahmin bivouac might have been forgotten except for William James Stillman, the organizer of the trip. Stillman captured the moment in an oil painting, The Philosophers’ Camp in the Adirondacks, which is part of the Concord Free Public Library Corporation’s art collection and normally hangs in the reference room of the Library. It is currently on loan, and can be seen in a special exhibit at the Concord Museum until September 4.

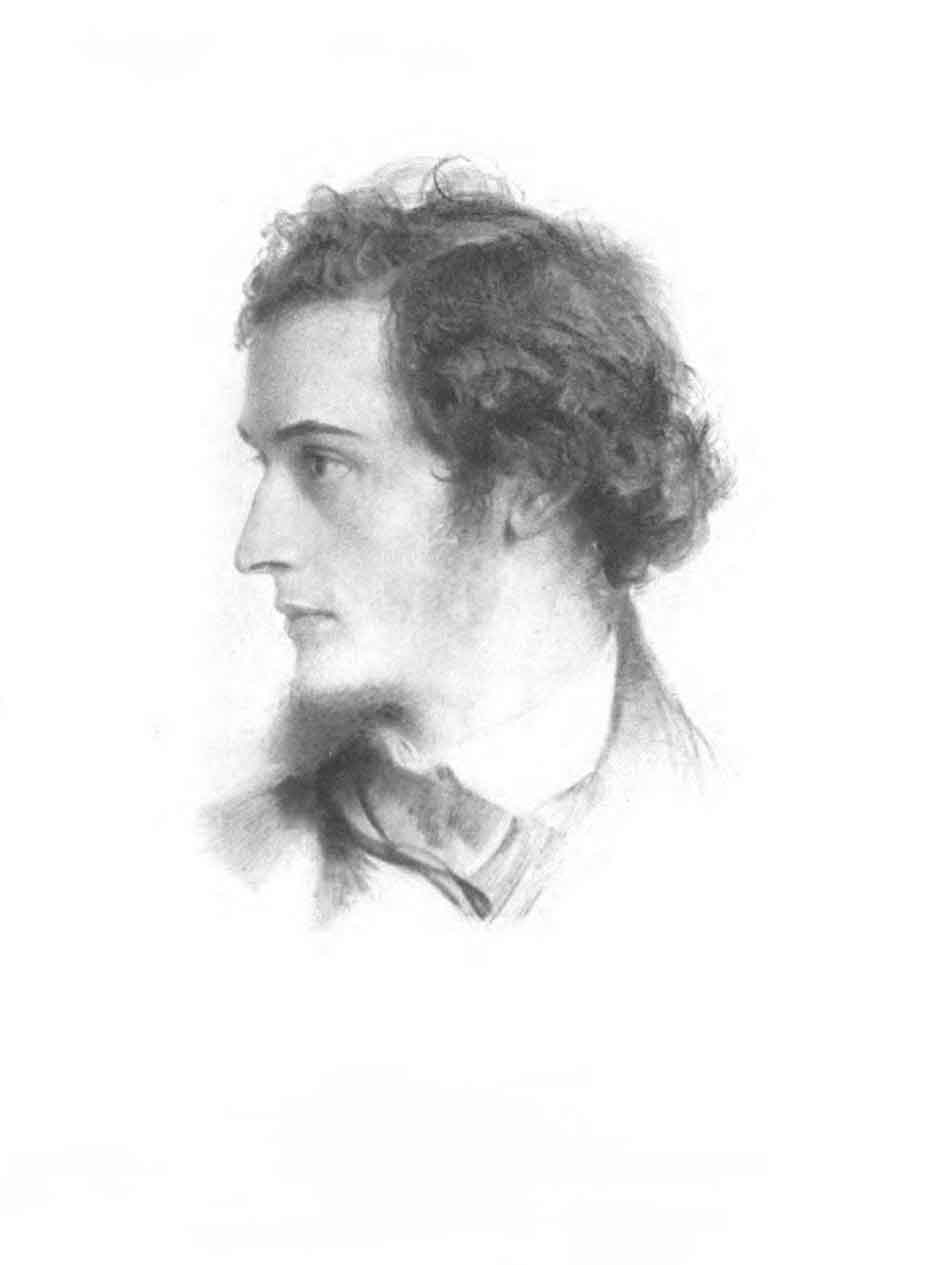

Samuel W. Rowse, William James Stillman, c. 1858. Reproduced as frontispiece in William James Stillman, The Autobiography of a Journalist. Vol. 1 (London, 1901)

| wikimedia.orgUnlike his fellow campers, Stillman could not boast a venerable New England pedigree or Harvard credentials. He came from Schenectady, New York, where his family struggled to pay for his college education. Setting his sights on a career in art, he studied with Hudson River School painter Frederic Edwin Church and in England with the Pre-Raphaelites Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais.

But it wasn’t his painting that brought him into the orbit of Emerson and company. In 1855, he founded a magazine he called The Crayon: A Journal Devoted to the Graphic Arts and the Literature Related to Them, and over its six-year run, it earned a national reputation for its fine, insightful writing. One of the early contributors to The Crayon was James Russell Lowell, scion of a prosperous family with roots in colonial-era Boston. Stillman and Lowell shared a sense of mission, of a world uplifted by art and literature. They became fast friends, and Lowell introduced Stillman to the Boston brain trust, including Emerson.

Both Emerson and Stillman sought transcendence in nature—the former in words, the latter in images. Stillman would travel for weeks scouting for unspoiled landscapes to fill his canvas. In 1854—just as Thoreau’s Walden was rolling off the press—he went to Saranac Lake in the Adirondack Mountains, where he boarded with a local family for the summer. He divided his time between painting and immersing himself in the sights, sounds, and textures of nature.

Stillman returned home to New York and set to work on The Crayon, but he couldn’t get the Adirondacks out of his mind. Under a pen name, he published an account of his travels called The Wilderness and Its Waters. He went back in the summer of 1856, and in 1857, James Russell Lowell went with him.

Lowell was a founding member of the Saturday Club, an informal group of prominent Boston-area men who met monthly for dinner and a spirited exchange of ideas about literature, art, science, government, and business (the Saturday Club launched The Atlantic Monthly, with Lowell as its first editor.) The club suspended its dinners during the summer, but Lowell’s enthusiasm for the virgin forests of the north inspired them to plan an August expedition they called the Adirondack Club.

Stillman knew the territory, so he went ahead to hire local guides for the visitors and to identify a remote campsite with abundant fish and game. He settled on a waterfront site at a pristine lake known locally as Follensby Pond. By the end of the first week in August, his nine companions had joined him there.

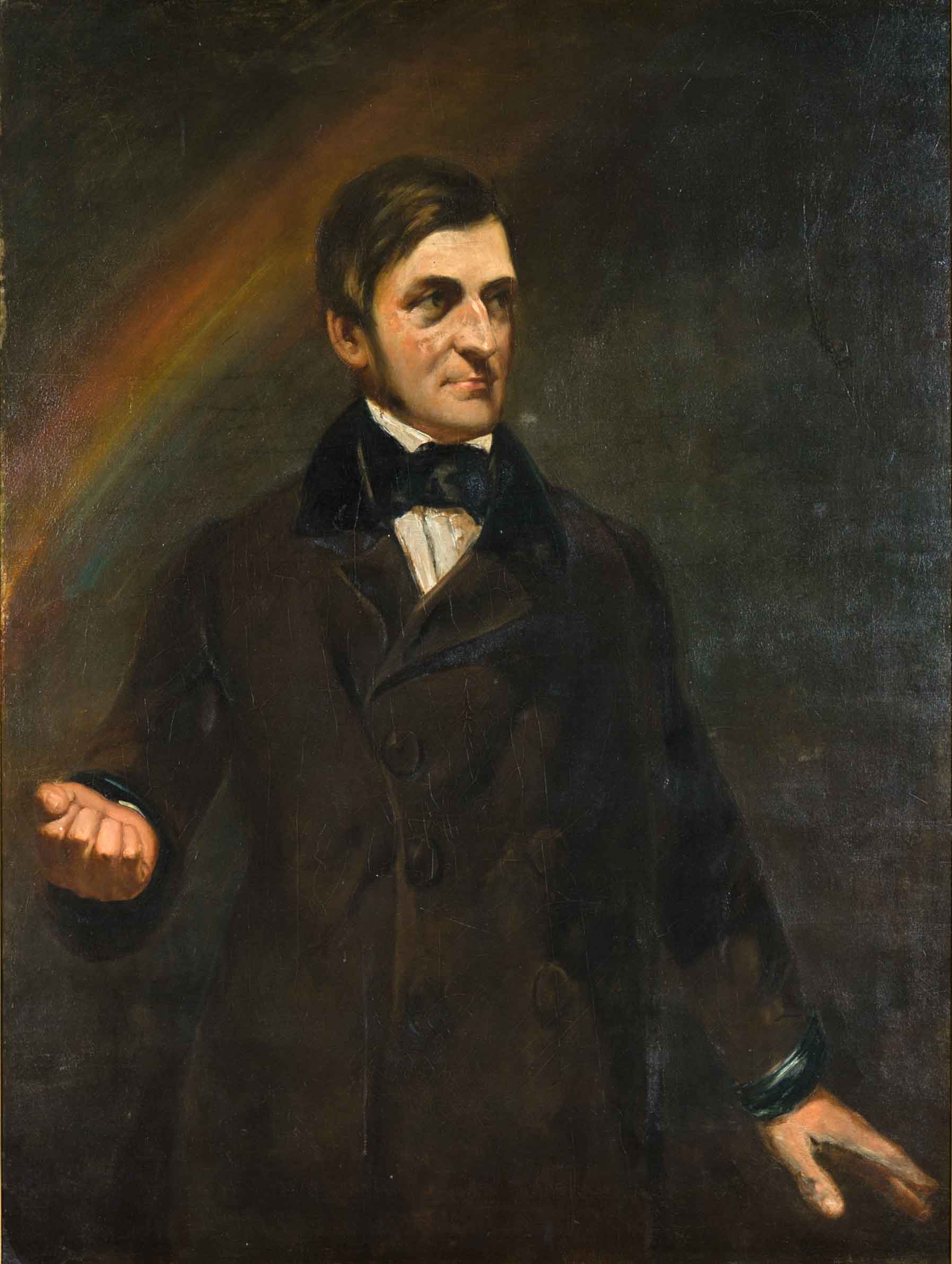

David Scott. Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1848. Oil on panel. Presented by Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar, Elizabeth Hoar, and Reuben N. Rice, 1873.

| Courtesy of Concord Free Public Library CorporationConcord was represented by both Ralph Waldo Emerson—at age 55, a revered man of letters—and Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar, a judge and former state senator whose antislavery activism helped to found the Republican Party.

Lowell’s Harvard colleague Louis Agassiz was at Follensby, too. In the years before Darwin’s Origin of Species and the American Civil War, the Swiss-born Agassiz was admired as a scholar of natural history and had become something of a national hero by spurning the offer of a prestigious post at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, choosing instead to remain a Harvard professor.

In our own time, Agassiz is remembered for stubbornly denying evolution and insisting that slavery was justified by the theory that Africans and Europeans were created separately. Less than three years before Fort Sumter, it’s hard to imagine him on cordial terms with committed abolitionists like Lowell and Hoar; perhaps their shared loyalty to Harvard allowed them to overlook his racism.

Agassiz made his time in the camp a working vacation. He relished the plentiful trout better as specimens than as supper. In Stillman’s painting, he can be seen in vest and shirtsleeves, dissecting a trout with the assistance of his Harvard colleague Jeffries Wyman.

The campers often started their day by shooting at targets and empty bottles. Stillman depicted this in the right side of his painting, with Amos Binney (son of a Boston doctor) taking aim, and Stillman himself beside him. Lowell is waiting his turn to shoot, and behind him is Concord’s Judge Hoar.

At target practice, Agassiz demonstrated great skill, but he didn’t like to shoot animals. Surprisingly, one specimen he did get was a peetweet (sandpiper) that Emerson shot in his only successful hunting effort. Emerson preferred to leave the hunters and fishermen behind while Stillman led him to a secluded bower for quiet contemplation.

Emerson imagined himself a latter-day Chaucer on a pilgrimage to a cathedral grown from the earth rather than hewn from stone. Stillman alluded to this by painting Emerson holding a pilgrim’s staff and standing apart from the others, “uplifted into infinite space” as he might have put it.

By the third week in August, their idyll was over. Plans were made to purchase land and make the Adirondack Club an annual event. A smaller group camped at a different site in 1859, but the campers’ attention was shifting to more urgent matters as the nation careened toward civil war. Stillman himself moved to Europe and new occupations as a diplomat and journalist, leaving his painting to remind us of the singular sylvan sabbatical for which he was the catalyst.

1 James Schlett, A not too greatly changed Eden: The story of the philosophers’ camp in the Adirondacks. Cornell University Press, 2016

All views expressed in this article are solely the author’s.