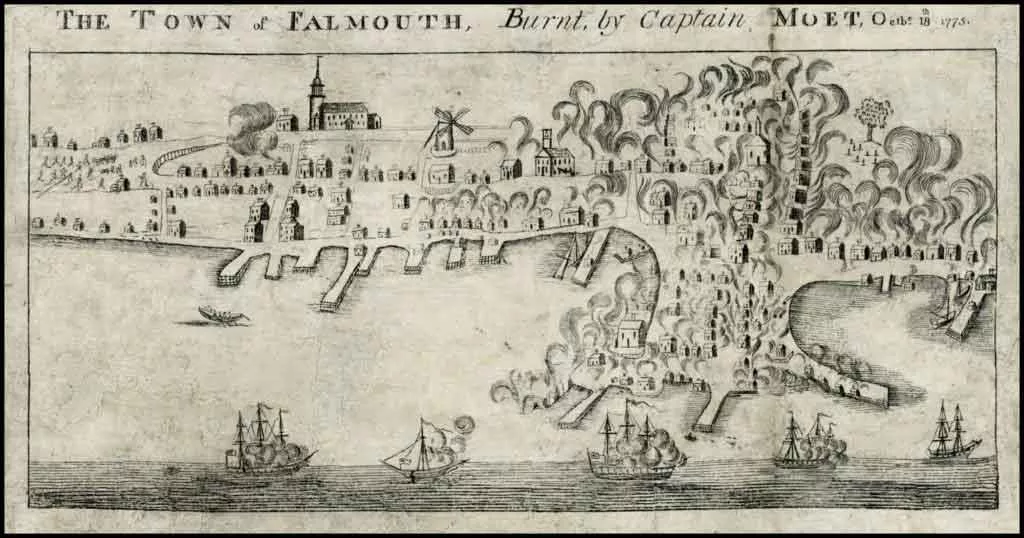

On the morning of October 18, 1775, the coastal town of Falmouth—now known as Portland, Maine—awoke to the ominous sound of British naval cannon fire. For over nine hours, incendiary shells, bombs, and grapeshot rained down upon the bustling seaport, igniting more than 400 buildings and leaving over 1,000 residents homeless on the brink of a harsh New England winter. The assault, commanded by Royal Navy Lieutenant Henry Mowat, represented one of the most brutal acts of retribution by the British during the early phase of the American Revolution. While intended as a punitive measure to quash the rebellion, the destruction of Falmouth ultimately fortified colonial resistance and contributed to a larger movement toward American independence.

The seeds of the attack were planted months earlier. In the spring of 1775, as tensions escalated between the colonies and the Crown, Admiral Samuel Graves—commander of the Royal Navy’s North American Squadron—began to abandon his earlier posture of restraint. The repeated embarrassment of British vessels by colonial privateers, along with provocations like the seizure of the Margaretta at Machias, Maine, and Lieutenant Mowat’s brief capture during “Thompson’s War” in May, pushed Graves toward more aggressive action.1 By late summer, the admiral conceived a campaign to make examples of coastal towns, which were viewed as hotbeds of insurrection.

Graves’ objective was clear: to terrorize rebellious communities through strategic naval bombardment and destroy their morale. On October 6, he issued written orders to Lieutenant Mowat to “chastize” a series of towns—including Marblehead, Salem, Newburyport, Portsmouth, and Falmouth—by burning buildings and destroying shipping. He cautioned Mowat not to occupy the towns or allow looting but made it clear that “vigorous efforts” were expected.2

Mowat had firsthand experience with Falmouth’s revolutionary fervor. The town had a long history of resistance, dating back to the Stamp Act, and had harbored Patriots who threatened British customs officials and publicly opposed the tea tax. Graves later cited Falmouth’s “insolence” and record of defiance as justification for its inclusion on the list of targets.

After delays caused by autumn storms and an aborted attempt to bombard Cape Ann, Mowat’s small squadron arrived off Falmouth on October 16. The fleet included the HMS Canceaux, HMS Halifax, HMS Spitfire, and the mortar-equipped HMS Symmetry, along with 100 marines. On the afternoon of October 17, Mowat sent ashore a written ultimatum warning residents to evacuate within two hours, promising a “just Punishment” in the name of the Crown. The message stunned the town. “Every heart was seized with terror,” recalled Reverend Jacob Bailey, a loyalist eyewitness. “The whole fleet stood directly up the river, and formed in line of battle before the town. We now plainly discovered one ship of twenty guns, one of sixteen, a large schooner of fourteen, a bomb sloop and two other armed vessels.”3

A small committee was quickly assembled to negotiate with Lieutenant Mowat, who consented to postpone the bombardment until the following morning if the townspeople surrendered their weapons. That evening, a handful of arms were handed over as a sign of goodwill. This led Lieutenant Mowat to proclaim, “If the town would surrender their cannon and musketry, and give hostages for their future good behaviour, he would delay the execution of his orders till he could represent their situation to the Admiral, and intercede for their final deliverance.”4

Realizing they could not meet Mowat’s demands, panic set in, and residents began to flee. At 8:30 a.m. the next day, the committee begged the Royal Navy for more time, asserting “that the whole town was then in the greatest confusion, with many women and children still remaining in it.”5 At 9:40 a.m., the red pennant was raised on the Canceaux’s mast, and the bombardment began. Mowat’s four ships launched approximately 3,000 rounds, including incendiary carcasses—iron shells filled with combustibles designed to set buildings alight.

Despite the poor quality of British munitions and a wind blowing away from the town, much of Falmouth was soon engulfed in flames. “Bombs and carcasses armed with destruction and streaming with fire blazed dreadful through the air,” Bailey wrote. “The crackling of the flames, the falling of the houses, the bursting of shells... threw the elements into frightful noise and commotion.”6

British marines landed in the afternoon to finish the job, torching any structures that had not yet caught fire. By sunset, the lower portion of the town, including its churches, courthouse, library, and waterfront, lay in ruins. Roughly three-quarters of Falmouth was destroyed. While there were no confirmed civilian fatalities, the loss of homes, livelihoods, and winter provisions were devastating. The town’s selectmen estimated losses of over £55,000.7

Though Admiral Graves considered the attack a successful demonstration of naval power, its political consequences were disastrous for the British. The American press seized upon the event, publishing multiple eyewitness accounts that framed the destruction as a barbarous act. The New England Chronicle condemned Mowat as an “execrable Monster” and declared, “No Mercy is to be expected from our savage Enemies.”8 George Washington, then commanding forces around Boston, called it “an Outrage exceeding in Barbarity & Cruelty every hostile Act practiced among civilized Nations.”9 In Philadelphia, members of the Continental Congress saw the attack as final proof that reconciliation was futile.

Mowat’s squadron returned to Boston having razed only one town, not the half-dozen targeted in Graves’ original orders. Illness, exhausted ammunition, and damage to the Spitfire made further operations untenable. Graves was relieved of his command that winter and no further punitive expeditions of this kind were attempted.

Ironically, the burning of Falmouth became a catalyst for colonial militarization. Just weeks later, the Continental Congress established the Continental Navy, its first modest step toward building a naval force of its own. Falmouth’s suffering was not in vain—it became a rallying point, a symbol of British overreach, and a warning that submission to the Crown offered no safety.

————————————————————————————————

1 Thompson’s War, which took place in May 1775, was a local confrontation in Falmouth (now Portland, Maine) between Patriot militia led by Colonel Samuel Thompson and British naval forces under Lieutenant Henry Mowat. Thompson’s men briefly captured Mowat and other British personnel in retaliation for the presence of the armed vessel Canceaux, causing widespread panic among the town’s residents. Though the prisoners were soon released, the incident deeply humiliated Mowat. 2 Donald A. Yerxa, “The Burning of Falmouth, 1775: A Case Study in British Imperial Pacification,” Maine History 14, no. 3 (1975): 119–161, https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1758&context=mainehistoryjournal; William Bell Clark, ed., “Vice Admiral Samuel Graves to Philip Stephens, October 9, 1775,” Naval Documents of the American Revolution, Vol. 2, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1966), 374. 3 Clark, ed., “Letter from Rev. Jacob Bailey, October 17, 1775,” Naval Documents of the American Revolution, 2:487. 4 Ibid, 2:488. 5 Clark, ed., “Lieutenant Henry Mowat to Vice Admiral Samuel Graves, October 19, 1775,” Naval Documents of the American Revolution, 2:515. 6 Letter from Reverend Jacob Bailey, Collections of the Maine Historical Society, 1st ser., V (1857), 442. 7 J. L. Bell, “A Tale of Two Cities: The Destruction of Falmouth and the Defense of Hampton,” Boston 1775 (blog), September 28, 2015, https://allthingsliberty.com/2015/09/a-tale-of-two-cities-the-destruction-of-falmouth-and-the-defense-of-hampton/#_ edn10. 8 New England Chronicle, October 19, 1775. 9 George Washington to John Hancock, October 24, 1775, “Founders Online,” National Archives, accessed July 2, 2025, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0210-0001.