In the fall of 1774, only months from the confrontation at the North Bridge, the Town of Concord was a thriving farming community and a regional trading hub accessible to Boston via two roads and with a population of nearly 1,500 inhabitants. The Town had grown gradually since its incorporation in 1635. Townspeople actively engaged in Town government and established businesses, schools, and churches to support the needs of its growing population. The inhabitants regularly squabbled over factional conflicts, but the community was harmonious in many respects.

However, the previous decade witnessed a steadily declining relationship between the American colonies and the British Empire. The effects of those increasing tensions were having an impact on communities in colonial America. Resistance to the acts of a progressively hostile British Parliament united townspeople along the Atlantic coast, including those residing in the inland community of Concord.

In an attempt to replenish their coffers after a costly French and Indian War (1754-1763), a conflict that determined authority over the territory of North America, Britain levied new taxes and increasingly tightened regulations on its American colonies, beginning with the Stamp Act (1765), followed by the highly unpopular Townshend Acts (1767). Finally, after the Boston Massacre (1770) and the colonists’ actions at the Boston Tea Party (1773), Britain imposed the retaliatory Coercive Acts (later known as the Intolerable Acts, 1774), which along with other measures, closed the port of Boston.

These acts provoked deep resentment in the colonies. In response, and with representatives from all territories, except Georgia, the First Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia, September 5, 1774, to draft a coordinated response to Parliament’s Coercive Acts.

Map of Concord, Mass Central Village as it was 1810-1820. Drawn from memory by Edward Jarvis, 1883.

| Special Collections, Concord Free Public Library

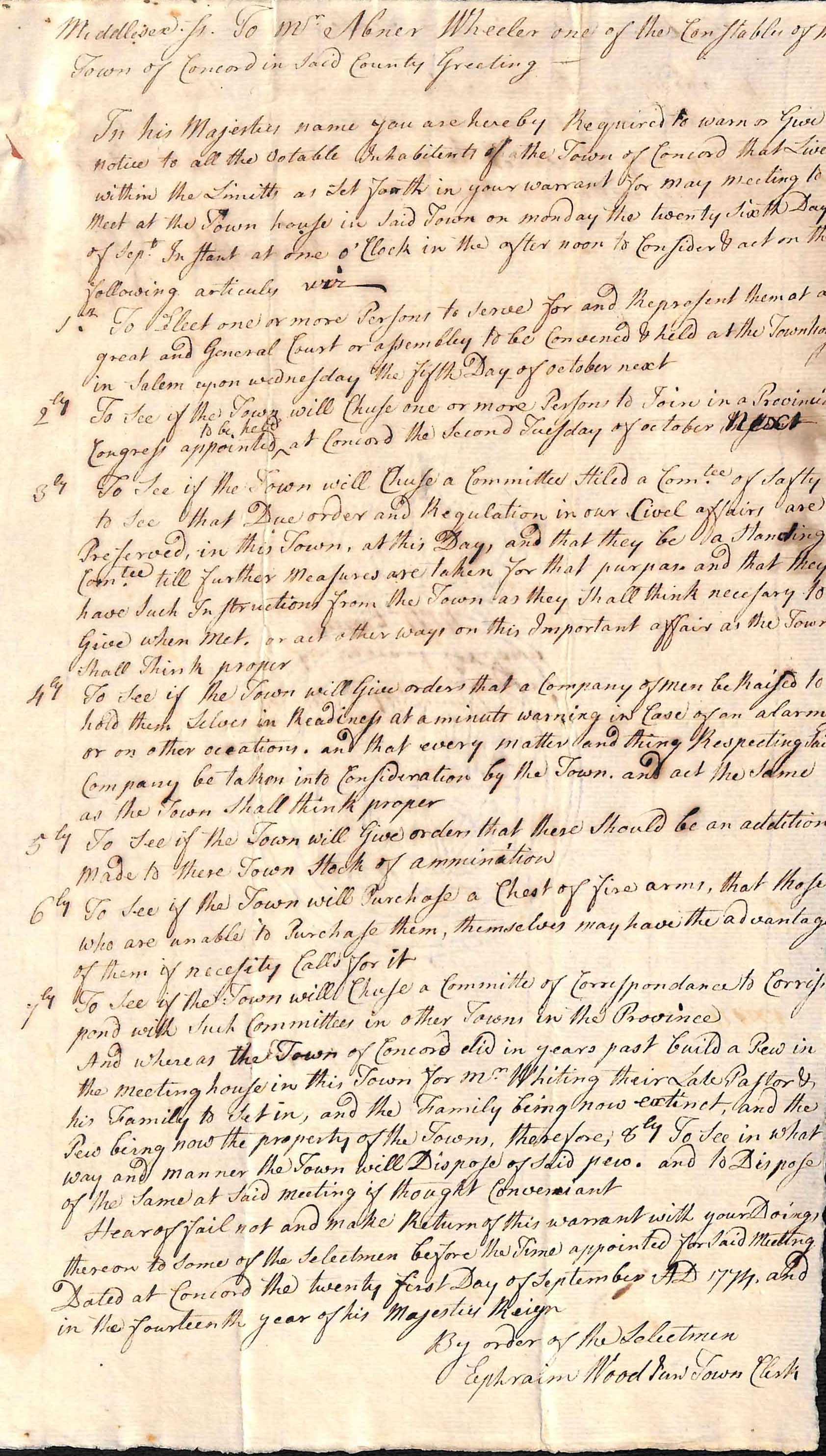

With tensions rising, on September 26, the townsmen of Concord took matters into their own hands and voted to raise a militia that could be ready “at a minutes warning in case of an alarm.” The Town also resolved to purchase ammunition and firearms to add to the Town’s stock.

Finally, in direct defiance of the Crown’s authority, the new Provincial Congress of Massachusetts, consisting of nearly 300 delegates, convened in Concord on Oct. 11, 1774. At the Wright’s Tavern, built by Ephraim Jones in 1747 but managed by Amos Wright since the early 1750s, the committees debated and drew up measures to end compliance with the Crown. Next door, at the First Parish Meeting House, the entire assembly deliberated and voted on the resolutions with John Hancock as president. Rev. William Emerson, an enthusiastic patriot, known for his inspirational sermons, officiated as Chaplain. The Provincial Congress assumed all powers to rule the province, collect taxes and supplies, and organize a military response.

Most consequential to Concord’s role in the events of April 19, Massachusetts’ Committee of Supplies, on November 7, 1774, recommended purchasing food and other provisions, including ammunition, and storing them at Worcester and Concord. While spies working for General Gage, the British Governor, kept him updated on the colonists’ amassing and storage of provisions, the colonists kept careful note of the movement of the Regulars in Boston.

In Concord, preparations continued throughout the mild winter and into spring. The minute companies exercised regularly. Provisions were plentiful. Was a crisis at hand? The anticipation was palpable.

To learn more visit the William Munroe Special Collections and Town Archives at the Concord Free Public Library.