Do you think about going south for the winter? So do many birds.

As the days get shorter and cooler, many of Concord’s resident birds get restless and think about wintering elsewhere. These birds migrate primarily because of food and not to avoid our cold winters. Many of the birds that migrate depend mostly on berries, seeds, and insects for their daily meals, but the insects crawl into the ground, dig under leaves, or drill under tree bark and sleep through the cold winter months. The migratory birds are not as well equipped as a woodpecker to hammer a hole in a tree to gather sleeping insects.

Woodpeckers account for about 30% of birds that stay. Other noticeable birds that stay are chickadees, cardinals, titmice, nuthatches, wrens, and the family of corvids: blue jays, crows, and ravens. The corvids will eat about anything, including carcasses. The birds that stay tend to form groups to help each other find food and warmth, which is why we see more of them together in winter.

Heron ice fishing

Birds that eat fish and frogs, like the great blue herons, have a problem dining when layers of ice shield the fish and frogs snuggle in the mud. The great blue herons are late to leave Concord but when the rivers and lakes ice up, they move a relatively short distance toward the ocean because it stays open and mostly free of ice.

Migration is a risky undertaking. Many of our birds do not make it to their destination, so they have to plan well to limit the risks. Birds that can soar, such as hawks, use the daytime thermals to carry them aloft. (If you go to the top of Mt. Wachusetts in October on a sunny day you will likely see many hawks getting lift from the air currents and soaring south.) There are also non-soaring birds that use the daytime thermals, such as swallows. These birds also tend to fly in the morning and then take a rest. It’s like people driving to Florida and stopping at motels along the way.

Osprey heading south

Geese and some other birds have found it very helpful to fly in a V formation to take advantage of a leader who breaks up the air currents. The leaders have to work harder so the geese take turns. Many of the smaller birds like warblers are not helped by thermals so they travel at night when the cooler air temperatures and smoother air are better for their energetic flights. All of these migrating birds need a lot of fat for energy, but those that travel long distances, such as one or two thousand miles, need a large percentage of their weight as fat to sustain themselves.

And that brings me to perhaps the most outstanding flyer of all birds, our ruby throated hummingbirds (the only hummingbirds in Concord), who fly over the Gulf of Mexico to South America at night. It helps that these tiny birds, usually weighing around three ounces, can store up to two ounces of fat to fuel their journey. And they can not only hover to gather nectar and insects, but also fly backwards. All that is hard to beat.

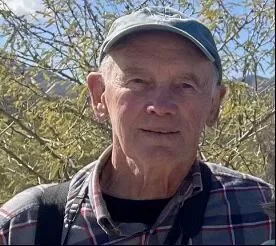

Photography by Dave Witherbee