After the Battle of Bunker Hill, British officials in Boston decided that several coastal towns to the north—including Salem, Beverly, Ipswich, Newburyport, and Gloucester—likely served as supply hubs for the American forces surrounding the city. As a result, these towns became important targets for British naval attacks and landings. Hoping to disrupt American supply lines, Vice Admiral Samuel Graves of the Royal Navy ordered Captain John Linzee of the fourteen gun sloop, HMS Falcon, “to put to Sea as soon as possible in his Majesty’s Sloop under your Command and cruise between Cape Cod and Cape Ann in order to carry into Execution the late Acts for restraining the Trade of the Colonies And to seize and send to Boston all Vessels with Arms Ammunition, Provisions, Flour, Grain, Salt, Melasses, Wood, &c &c.”1

The Falcon had already caught the attention of Massachusetts colonists, as it had participated in the bombardment of the American position during the Battle of Bunker Hill. Now, it had set its sights on coastal Essex County. On August 5, 1775, HMS Falcon entered Ipswich Bay and anchored at the mouth of the Annisquam River. Captain Linzee quickly dispatched a landing party with orders to seize sheep from a nearby pasture to supply the ship with mutton.

Major Peter Coffin, a local farmer, suspected the British intent and quickly alerted laborers on his land and neighboring residents. Armed with muskets, the small group took up concealed positions behind dunes and opened fire as the ship’s boat approached. Believing a full company of militia lay in ambush, the British officer leading the landing party abandoned the mission and returned to the Falcon empty-handed.2

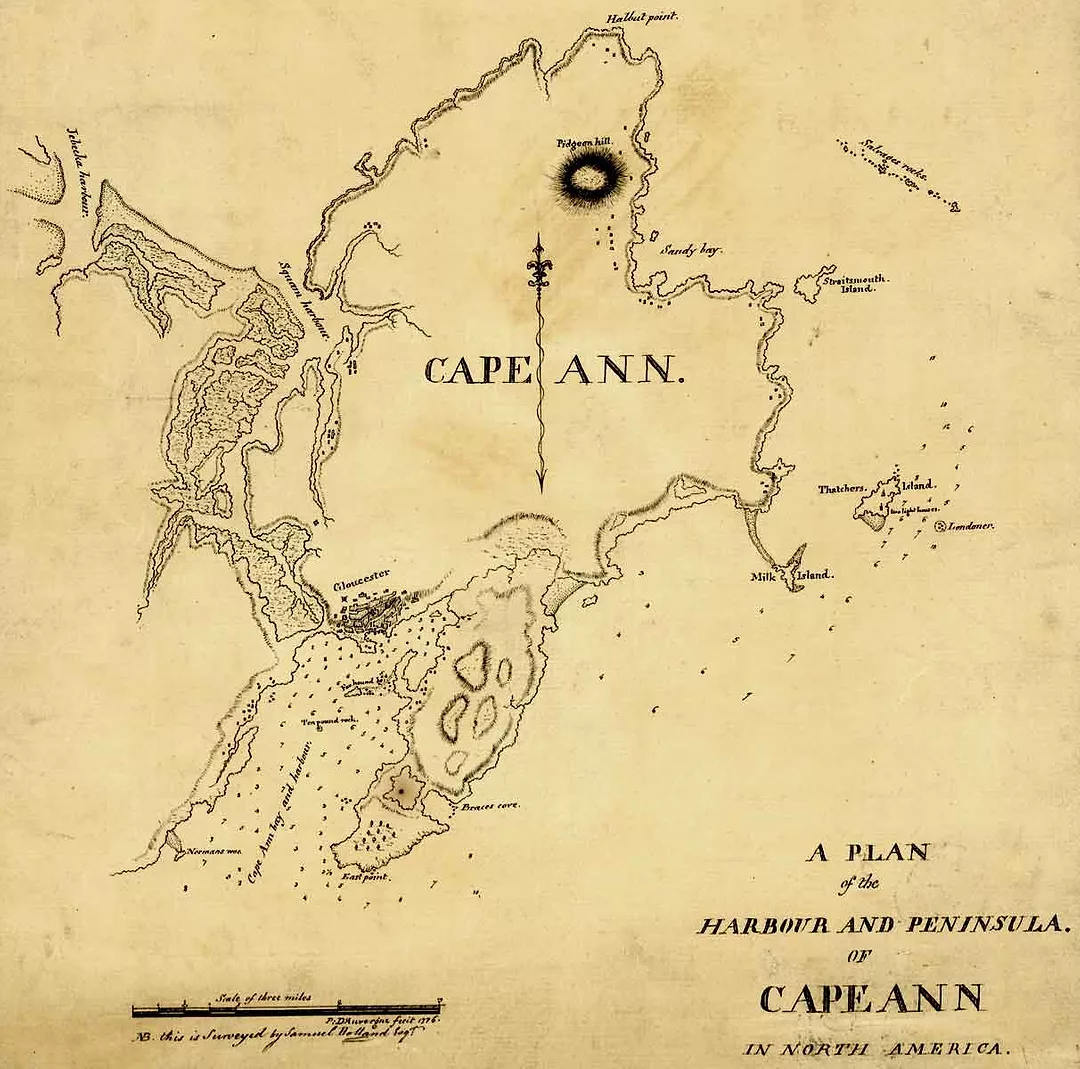

For the next three days, HMS Falcon patrolled the waters off Cape Ann, aiming to capture colonial merchant ships headed for Salem or Newburyport. On August 8, Captain Linzee spotted two schooners—likely coming from the West Indies and en route to Salem. He seized one as a prize and chased the other into Gloucester Harbor, where the fleeing vessel ran aground near Five Pound Island. The unusual sight quickly caught the attention of Gloucester residents, who soon saw the British warship towing a captured schooner. Recognizing the danger, alarm bells from the town meeting house began ringing, calling the militia to assemble.

Undeterred by the alarm bells, Linzee ordered his ship into Gloucester’s harbor. He quickly seized a nearby dory fisherman named William Babson and told him to pilot the Falcon into the harbor. The captain warned that if Babson did anything “to let the ship strike bottom, I will shoot you on the spot.”3 The sloop dropped anchor between the headland called Stage Head and nearby Ten Pound Island, sending three whale boats with thirty-six sailors and marines toward the grounded schooner.

On shore, the local militia prepared to prevent either seizure of the schooner or a British landing in town. Though they lacked cannons and had little powder or shot, the residents managed to mount a pair of swivel guns on makeshift carriages and positioned them for defense.

As the naval boats closed in on the grounded vessel and began to board, musket fire erupted from the shore, killing three sailors and wounding a lieutenant in the thigh. The barges withdrew with their casualties, leaving much of the boarding party behind on the schooner. In response, Linzee sent the previously captured schooner—now manned by a British prize crew—along with several small boats, all ordered to fire on any “damned rebel” within range. He also ordered a cannonading of the town by the Falcon in an attempt to draw attention away from the schooner, but “the Rebels paid very little Attention to the firing from the Ship.”4

While the boarding party remained pinned down on board the schooner, Linzee dispatched a landing party to burn the town. According to a later report from the Falcon captain, “I made an Attempt to set fire to the Town of Cape Anne and had I succeeded I flatter myself would have given the Lieutt an Opportunity of bringing a Schooner off, or have left her by the Boats, as the Rebels Attention must have been to the fire. But an American, part of my Complement, who has always been very active in our cause, set fire to the Powder before it was properly placed; Our attempt to fire the Town therefore not only failed, but one of the men was blown up and the American deserted.”5 Enraged, Linzee dispatched yet another landing party with orders to burn the town by torching the fish flakes. However, Gloucester militiamen quickly swarmed the landing party and took them prisoner. As Linzee would bitterly report, “A second Attempt was made to set fire to the Town, but did not succeed.”6

At four o’clock in the afternoon, Linzee made one final push to seize the schooner and rescue his captured sailors. As several boats closed on their targets, the Falcon continued to pour broadsides into the fishing village. Surprisingly, the militiamen did not yield. As Gloucester’s Reverend Daniel Fuller recalled, “Lindsey, Capt of a man of war, fired it is supposed near 300 Shot at the Harbor Parish. Damaged ye meeting House Somewhat, Some other buildings, not a Single Person killed or wounded with his Cannon Shot.”7

A wounded officer and a few men were rescued from the grounded schooner. The remaining men aboard—including several impressed Americans—were eventually captured by the militia. By 7 p.m., all of the British small boats had been taken. In a final effort to recover his men, Linzee sent the prize schooner into the harbor. However, he later reported his belief that the original crew had seized the opportunity to overpower the British prize crew and retake the vessel. As Linzee explained, “After the master was landed, I found I could not do him any good, or distress the rebels by firing, therefore I left off.”8

The ship-to-shore engagement resulted in a decisive American victory. Gloucester’s men recaptured both schooners and took thirty-five British sailors, several wounded, with one dying shortly afterward. Twenty-four of the captured men were sent to the American prison camp in Cambridge. At the same time, local sailors who had been previously impressed into the British Navy were released and allowed to return home.

Captain Linzee’s unsuccessful raid on Gloucester influenced subsequent British naval reprisals. In October 1775, Admiral Graves directed Captain Henry Mowat to punish various coastal towns in New England, using Linzee’s defeat as justification for these actions. Although Gloucester was among the targeted locations, Mowat opted against attacking it, reasoning that the town’s buildings were too widely scattered for an effective bombardment. Instead, his decision to incinerate Falmouth, now known as present-day Portland, Maine, was pivotal in prompting the Continental Congress to establish the Continental Navy.

————————————————————————————————

1 William Bell Clark, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution volume 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1964), 900 (NDAR). 2 See Louis Arthur Norton, “Falcon Fans the Flames of Revolution: The Misadventures of Captain John Linzee,” Journal of the American Revolution (War at Sea and Waterways, 1775–1783), November 9, 2021, All Things Liberty, accessed July 1, 2025. 3 Joseph E. Garland, The Fish and the Falcon (Charleston SC: The History Press, 2006), 109. 4 John Linzee to Samuel Graves, August 10, 1775; Garland, The Fish and the Falcon, 109. 5 Ibid. 6 Ibid. 7 Diary of Reverend Daniel Fuller, Pastor of the Second Parish Church, in James B. Conolly, The Port of Gloucester (New York, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Company, 1940), 59. 8 Garland, The Fish and the Falcon, 116.